My favourite copy, part 1

Paul Belford is currently writing an excellent blog. It explains in detail why certain print/poster ads were so good, but with a focus on the art direction.

I think the ideal complement would be a similar blog about copy, written by an equivalent master of the art form.

But in the absence of Nigel Roberts, Mary Wear or Richard Foster, you’re left with me. Sorry.

I know I’m not a ‘great’ in the sense that I’m not in the Copy Book, not have I won a Copy Pencil, but until I start asking people far better than me to write guest posts, this is it. Feel free to stop reading now, or carry on and see if you agree with my assessment.

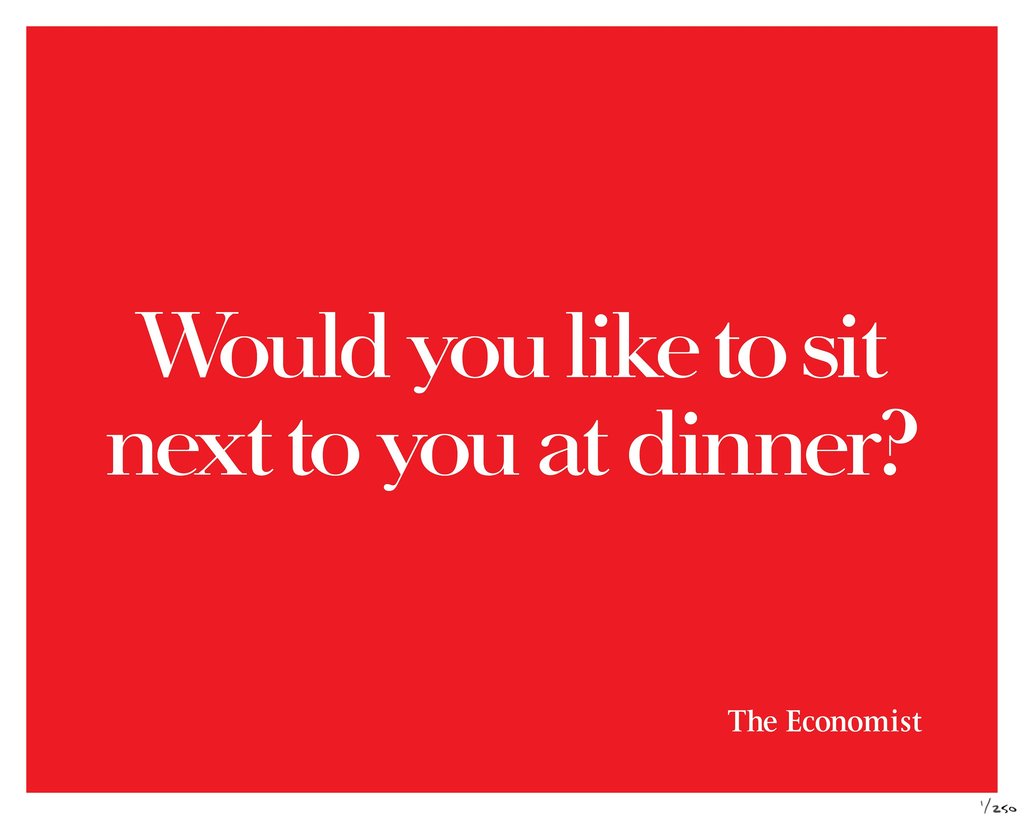

Now that I’ve got the admission of under-qualification out of the way, let’s start with the ad on this page.

Of course, choosing one of David Abbott’s Economist ads is like shooting a Great White in a barrel, but let’s not ignore the perfect just because everyone knows that it’s perfect. The point of this post is to explain the reasons behind the perfection.

Longtime visitors to this parish will be aware that I trod the boards of this account in my youth. That qualifies me to explain that it’s an arse to work on. Too many excellent predecessors. Too much competition from one of the best creative departments in the business. Too many areas already explored, and therefore obsolete. Smart Cars, Smarties, pictures of brains, Brains from Thunderbirds, Latin, lightbulbs, Venn Diagrams, Blue Plaques, paint colours, Einstein, shredders, keyholes, jigsaw pieces, long headlines, pros and cons, pregnant pauses etc. etc. etc.

And yet the stone would always accommodate one more squeeze.

I’m not the only one who would actually trawl through a thesaurus looking for different angles on ‘read this and be successful’. Then again, Jeremy Carr was apparently at lunch with the Economist account team when the waiter asked, ‘Still or sparkling?’ and unwittingly wrote a headline for the next batch.

But back to, ‘Would you like to sit next to you at dinner?’ Why did I chose that one over all the other superlative Economist lines?

First, because it expresses a truth. All the best art does this, but to convey so much of life, and inspire so much introspection in ten simple words is remarkable. Yes, we’ve all considered this situation for our own selfish wants, hoping our next-door neighbour won’t bore us to death over the seafood risotto, but how many times have you considered it from the other side? Think about it right now: have you ever been the dreaded, unwanted dinner party partner?

Now you’re considering it: how interesting am I? How funny and insightful are my anecdotes? How witty is my repartee? How many subjects do I feel comfortable discussing? Am I up to date on the current affairs, or am I going to look hopelessly out of touch?

A marvelously subtle dagger’s jab of fear, and expressed without the distracting self-congratulatory ‘cleverness’ of a pun.

Now I love an Economist pun as much as the next man, so long as the next man is Dave Dye, who hates them so much he was willing to piss off both his boss and his boss’s boss just to avoid running one. I think they’re only good if they also express a truth (‘Great minds like a think’), otherwise they tend to go an inch deep, but no further. Punless truths get to the point faster by removing extraneous obstacles of expression.

The edge of a conversation. The loneliest place in the world.

Lose the ability to slip out of meetings unnoticed.

What exactly is the benefit of the doubt?

So the insight is compelling. What about the way it’s expressed?

Well, no one ever says ‘Would you like to sit next to you at dinner?’, but they might say, ‘Would you like to sit next to Trevor/Susan/Joe at dinner’. So Mr. Abbott has taken a familiar sentence construction and turned it on its head. ‘Would you like to sit next to you’ sounds just odd enough while remaining easy to understand. This makes it penetrate a little further: your brain races away with the presumed ending, but then it has to put its brakes on and recognise the difference. So it thinks harder, stays with the ad longer, and goes through a process that lives longer in the memory. The line wasn’t just noticed, it was implanted.

Tonally, it’s perfect. The meaning of the line is, ‘Are you boring?’, but it’s said in a way that leaves it all up to you. It’s not nastily implying that you are a dullard; it’s merely asking the question. It welcomes you by presupposing that you are the kind of person who has friends that might invite you to dinner. It also suggests that this has happened to you often enough that you understand the situation, and its potential to go wrong. It invites you in with warmth, then turns the whole thing on its head by asking if you’re worthy of that invitation, all in ten words.

It also works so well with the construction of the entire ad: ‘Would you like to sit next to you at dinner? The Economist’. Question and answer, problem and solution. Twelve words that sell you a magazine with deft simplicity.

How else could it have been written? Perhaps something addy that tries too hard, such as, ‘What do you bring to the party?’. Or a ham-fisted attempt at the effortless elegance: ‘Would someone be happy to sit next to you at dinner?’. How about, ‘Be first on a list of dinner party guests’?

All dreadful, but they demonstrate how having the thought isn’t enough. The idea of being an interesting dinner party guest is the first part of the process. The real skill is in landing the plane so well that you get a round of applause from the passengers.

That’s what David did: concept and execution in perfect harmony.

He also made it look effortless. Then again, if you’ve read anything about how he worked, it probably was.

To get a poster line picked for The Economist was a bucket list moment of my career. ‘The pregnant pause. Make sure you’re not the father’ was put down with hundreds of other executions, but this one made the grade. Ron had Already sorted the art direction and the book beckoned. I can die a happy copywriter now ?

As David Ogilvy said, a great copywriter is both a poet and a killer. Perhaps that’s at the heart of Abbott’s greatness. “What oft was thought, but ne’er expressed” {Pope, I think].