Plenty of paths to perfection

When Stanley Kubrick was making The Shining…

He recorded the sound of a typist hammering out the words “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy”, because he thought the sound each key made on a typewriter was slightly different and he wanted complete accuracy. To make sure that the line was as effective in foreign versions, Kubrick painstakingly translated it into idiomatic German, French, Spanish and Italian and re-shot the scene, placing the translations in the typewriter for Jack’s wife Wendy (played by Shelley Duvall) to find. The Spanish phrase “No por mucho madrugar amanece más temprano” (No matter how early you get up, you can’t make the sun rise any sooner) captures the tone of crepuscular horror perfectly.

That’s just one of the many stories of Kubrickian perfectionism. He never compromised, went to extraordinary lengths and drove his actors crazy with endless takes. So that’s how you achieve excellence, isn’t it? You obsess over details and never let up in your monomaniacal drive to achieve your singular vision.

Maybe.

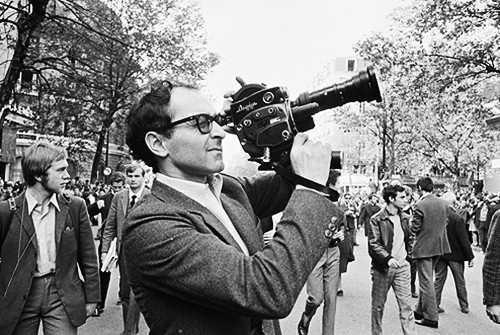

Jean Luc-Godard, a similarly revered director did nothing of the sort. In making his classic Breathless, he ‘wrote the script as he went along‘. ‘Filming began on 17 August 1959. Godard met his crew at the Café Notre Dame near the Hôtel de Suède and shot for two hours until he ran out of ideas.’ ‘Actor Richard Balducci has stated that shooting days ranged from 15 minutes to 12 hours, depending on how many ideas Godard had on a given day‘. ‘(Director of Photography) Coutard said that when (producer) de Beauregard encountered Godard at a café on a day on which Godard had called in sick, the two engaged in a fistfight.’

In addition, like many European directors of the time, Godard employed American actors who did not speak French/Italian/Spanish and simply dubbed the appropriate language over their English line reads. Jack Palance in Le Mepris, Burt Lancaster in Il Gattopardo, Alain Delon in L’Eclise… I just want to emphasise that these are some of the greatest films of all time, and the sound doesn’t match the mouth movements – and there’s not even a pretence of an attempt to do that!

In later films they worked out that the mouth shapes for the Italian/French words could be matched to the mouth shapes of English numbers, so an English actor’s line would be ‘Three, seventeen, nine, four, twelve’. Not the actual lines with the emotional content of the correct words, but a list of numbers.

Let me add still further: Fellini liked to direct as the acting was happening. He would shout at the actors as they were reading their lines, even the Italian ones. This meant that all the dialogue was post-synched, so it had none of the ambient sound, and didn’t match perfectly.

All that is to say that Kubrick (and other great perfectionist directors, such as Ozu, Chaplin and Malick) would presumably have had a fit about any of the above. If he insisted typewriter sounds were perfect, can you imagine him dubbing over a carefully chosen actor’s voice so it didn’t match the mouth movements? Or making up the story as he went along? Perfection and spontaneity are not easy bedfellows.

So which is best? Perfectionism or looseness? If you squeeze too hard, do you destroy the delicate object in your hand? Or is it possible that the wrong colour blouse or a misplaced apple can destroy or compromise an entire creative vision?

With so many greats on either side of the argument, it might be better to define perfection. What Kubrick et al would see as the essential control of every element until it matches the vision in their head, Godard might see as a lighter, more emotional expression of an artistic idea, with the spontaneity being as crucial to him as the control was to Kubrick.

I was involved in making two ads for the same big client a while ago. One had a budget of millions, was minutely planned and examined, and involved thirty agency staff. The other had a budget of ten thousand dollars, was briefed in by two mid-level creatives, and forgotten about until the directors sent in the final result. Both were excellent, and I think each would have suffered if they’d experienced the same level of budget and attention as the other.

I know of excellent art directors who are happy to brief a photographer then wait till he sends the finished shots in. I also know of excellent art directors who minutely micromanage their photographers. I also know of excellent art directors who work wonders with stock shots.

I know of excellent copywriters who pore for days over every syllable in a three-word line. I also know of excellent copywriters who find great phrases hidden in company brochures. I also know of excellent copywriters who crank out hundreds of words as easily as they breathe.

So there’s no agreed-upon path to greatness, and the important thing about that is the fact that your method might be the best route to the best work, but so might anyone else’s. That’s not to say that sitting around doing nothing is the most likely way to win a Cannes Grand Prix, but bunking off to see a movie could prove as effective as pulling an all-nighter. Letting a top director do their stuff could be as useful as constantly looking over their shoulder and insisting they do fifteen more takes. Nailing down a script might be a good idea, but so might turning up with an outline and seeing what you might get from a bit of improvisation.

Try a bit of Kubrick, then maybe go for a touch of Godard. There’s no right or wrong; only what works – and many, many things can work brilliantly.