Newish things that haven’t made advertising better, part 7: complexity.

Advertising is an industry fueled by simplicity. At our best, we create simple messages, via a relatively simple process: work out what a client wants to say, say it persuasively, get that message out to the people they want to hear it. The more we add complexity, the worse our output becomes.

Complexity is difficult to grasp, annoying to process and off-putting to engage with, but for the last twenty years it’s become a more significant element of what we do.

So join me as I slip back through the mists of time, to a gentler, simpler epoch…

When I started off there were generally four media channels: press, posters, TV and radio. (Coming up on the outside were the ‘ambient’ media opportunities, but let’s face it, most of these were awards-fodder bullshit.)

Let’s just think back to that time with a collective ahhhhhhhh…, as if we are now sinking into a soft leather armchair, accompanied by a Whisky Sour and a bowl of kettle chips. Just imagine: if you had to think up an advertising idea, it only had to exist in one of those four forms, two of which were pretty similar to each other.

The work was better then (see all the other posts in this series). That’s not just my opinion, there’s a graph I can never seem to track down (if any of you have it, do send it my way) which has collated many answers to the question, ‘Do you think the ads are better than the TV shows?’. The line starts at a healthy spot in the early nineties, with quite a few people saying yes. Then it starts to head downwards at the kind of pace that would put the shits up Matthias Mayer. Yes, the TV shows have improved, but let’s not kid ourselves: the ads have become worse.

Is that because of complexity alone? Of course not. Budgets, brain-drains, the internet, open-plan offices, the rise of the holding company, globalisation etc. have all played their interconnected parts, but at the root of everything else is the spiraling growth of an overall complexity.

Let’s return to those media channels. With only four, they could, to a certain extent, be mastered. Some of us were informally allowed to specialise still further, with creatives being recognised for their abilities in TV or press, and fed more exclusively with those briefs. But most of us might be handed a poster brief one day, and a radio brief the next, or we’d be asked to come up with a mixed-media campaign that had to work across all four channels.

The advent of ‘digital’ changed all that. like water seeping in under a closed door, the digital briefs started to become more numerous and take on a greater significance. Banners started off as a little joke, where you’d kind of pat them on the head and send them on their plucky way before returning to the real stuff of billboards and TV commercials.

But then they became a more integral part of things, added to many briefs, and not to be sniggered at. In 2007, industry commentators told us that if we didn’t have digital in our book we were in danger of becoming dinosaurs. Places like R/GA demonstrated the need for explaining things like ‘UX’ on lots of whiteboards, and we were certainly not in Kansas anymore.

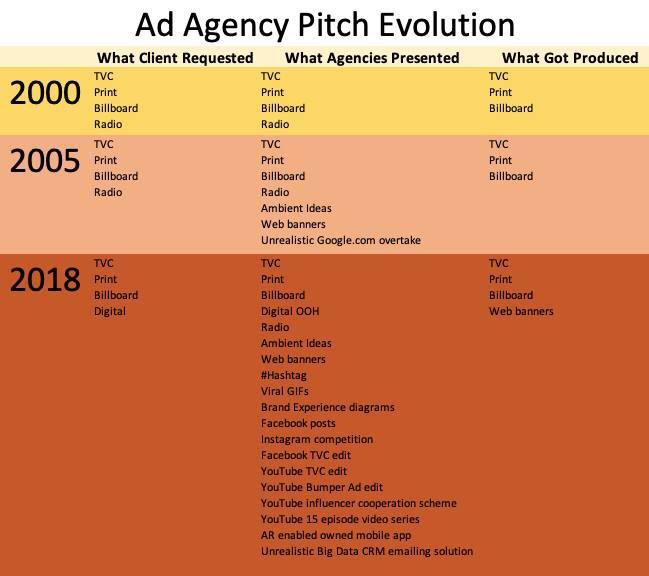

Year after year, digital rose, and with it, complexity. Here’s a chart that sums it up nicely:

To me it seems self-evident that the ability to maintain quality over those 15-20 channels is far harder than doing so over the span of the original four.

Press, posters, TV and radio still need to be fed and watered, so we’re clearly having to spread the same talent and money over a much larger area. Except it’s not the same talent and money, is it? The grind, and the fewer opportunities to produce big, famous work, has put many people off taking up residence in adland, so the talent is of a lower quality. And the fun and games of neo-liberalist capitalism have left the financial side of things… now, what’s the technical term? Oh yes: fucked. A tweet from Saturday should illustrate this neatly:

So there’s less money and less talent, but far more stuff to make.

That situation has complicated staffing. We now have comms planners, digital production, digital strategy, gif makers, social ECDs, CRM experts, search arms of media companies, influencer network advisers, content producers and many more. All paid, on average, less than their counterparts would have been a decade earlier.

And we have more agencies for those jobs. Some big companies have consolidated the new needs into their existing departments, or created new departments, and a bunch more complication. But many new, specialised companies have arrived to cover the new disciplines. And then they have to try to work with each other to span the new varied ‘needs’ of the average client, complicating their own working systems, especially as each was trying to eat each other’s lunch and protect their own.

Adding these layers has taken attention and money away from the ads, which themselves have become more complicated: one ad in one medium keeps an idea simple, but each new medium adds a additional degree of complication in terms of maintaining the integrity of the idea. It may be the case that the new channel expands the depth of a campaign, but it also adds a need for other skills, along with their attendant practitioners, each with a specific set of opinions and agendas. Extra human beings can complicate things at the best of times. These are not the best of times.

Of course, when I said ‘one ad in one medium keeps an idea simple’, that’s much more in theory than in practice. Clients and planners have always struggled to keep to a single-minded proposition, explaining that ‘We’re the fastest safe car in the world’ is single minded, while giving you a withering look of condescension. But when you proliferate that multiplicity over numerous strategists, channels, comms plans and agencies, you vastly increase the potential for complication.

We can say that in India but not in Brazil, so change it. They’ve moved the media budget from CRM to social, so change it. The experiential agency just had a similar idea turned down, so change it. Two planners from the telco hub in Detroit like the idea of ‘conquering fear’, while two others at the media agency in Austin prefer ‘expanding bravery’, so change it, etc.

Mix that lot up, chuck it out all over the place for all sorts of people, and good luck making it simple enough to be effective.

I get that we need to be where the eyeballs are, but the eyeballs are now everywhere, and each location has its own best-use advice. You might think a banner is just a digital location for a poster, but is it rich media? Do you go programmatic or white list? Which shapes and sizes have you bought? Does your line or visual fit all of them? If they’ve just been added to the media mix, have you bought the talent out to a sufficient extent? What are the KPIs? How do you measure them? When will it reach the desired clickthough rate? Is the Shopify UX ready? How do you know if the increased sales came from the banner or the radio ad? Does the smaller additional media budget justify enough production cash to make the ad properly?

And on, and on, and on, through many clients, CDs, creative agencies and media agencies, each with different answers that might change from hour to hour, or even from minute to minute.

And I haven’t even got into the different payment terms, or how HR staff have keep up with the needs of the people required to produce this campaign, but not that one. Maybe you can maintain a flexible, freelance workforce, but do they deserve healthcare, or an invitation to the agency Christmas party? What about their plus ones? What venue do we book if they all say yes? Can the budget stretch to that? If that means sausages instead of prawns, how will that affect the vegans?

See what I mean? Questions on questions on questions, all of which need to be answered, but many of which are tedious, time consuming and expensive, adding further to the complication.

Ernest Hemingway, that stellar practitioner of utter simplicity, once wrote the following exchange:

“How did you go bankrupt?”

“Two ways. Gradually then suddenly.”

And that’s how we found ourselves in a web of complexity more fiendish than a dozen intertwined spider webs.

I have no idea what the solution is, but when we finally come across one, I bet it’s simple.