The Dubious Reliability of Case Studies

I was in Cannes in 2008. That year’s winner of the Outdoor Grand Prix was the game-changing, category-bending, convention-smashing HBO Voyeur. It was far too multi-layered to be self-explanatory, so it needed a case study, and here it is:

TL/DR: HBO is all about telling stories so they did that as a live event projected onto the back of a New York building, then added another layer online.

Pretty much every entry for every award now has a case study (side note: judging these things is exhausting. I know you get two minutes to use, but a juror will be delighted if they’re asked to evaluate a concise 1:20 instead), but this was one of the earlier ones.

The reason I remember it is because I was standing around at some party, discussing it with a friend, and he said, ‘Have you watched any of the actual stories?’. I said that I hadn’t and he laughed. ‘They’re rubbish! Watch one. They’re complete crap’.

I have no idea if they are good or bad or somewhere in between because even though he told me to have a look I simply couldn’t be bothered. Life was/is too short. But even now, fourteen years later, I remember that this event won awards all over the world, and yet there was a good chance the jurors didn’t even know what they were judging. If they just watched the case study, they experienced about 5% of the actual ‘ad’.

And what is a case study but an ad for an ad? It’s aimed squarely at a small audience of senior advertising creatives who are probably less than enthused at having to watch yet another little film about something they can never fully understand. Does it have that stat about ‘media impressions’? Tick. Does it have a (probably local) news anchor covering the story? Tick. Does it have a graphic of lots of Tweets? Tick. Does it have impressed passers-by taking a good look at the giant thingy hanging off the side of the building? Tick.

Of course there’s a good reason for all this: ads these days need to demonstrate their 360-ness in order to look good to a jury. Then they need to express the nice thing they did for the planet. Then they need to convey some stats to show how effective it was. And all of this because the juror almost certainly never saw it in the real world, because a) It probably ran in a country they don’t live in, and b) It probably ran in a relatively obscure digital/experiential media space.

So the jurors have to rely on what the creatives decide to tell them through the medium of the video. But let’s not forget that those creatives work in – oh yes! – advertising, where they are paid and trained to present the best-case scenario of a product/service/situation all day, every day. Here’s their chance to make an ad about an ad, and that will inevitably mean spin upon spin.

I think jurors are starting to become more cynical and jaded about this, so the canny ones probably learn to screen out the more obvious bullshit, but they can never know for sure, so they probably let a lot of things slide.

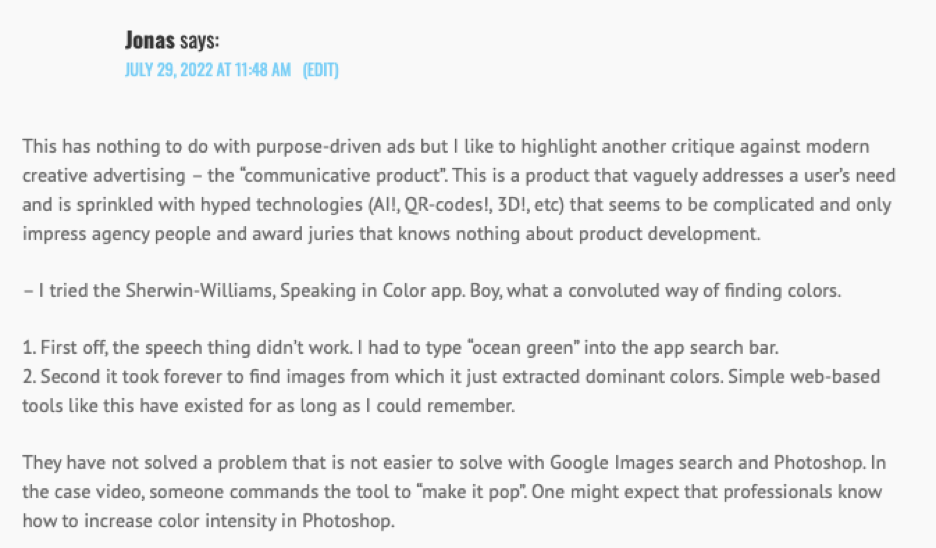

Then again, I was prompted to write about this by a comment on my recent post about purpose-based Cannes Grand Prix winners:

Here’s that case study:

Jonas has kindly done the work that the jurors clearly decided not to, and discovered that this best of the best of the best initiative was actually a bit crap. But now and forever it is a CGP winner, so the bullshitting creatives achieved their goal.

Do I expect every juror to forensically examine everything they award? Of course not; it’s an arduous-enough task without making it ten times harder. But until people delve properly into case study claims, creatives will fluff up the excellence of their work as much as they think they can get away with.

I’m also aware that the alternative would be kind of weird: ‘Shall we say all the best things we can about our campaign, adding the most positive interpretations of its effectiveness wherever possible?’ ‘Nah. Let’s be scrupulously honest, humble and self-deprecating and hope that wins the day’. This is now where we are, so you have to play the game like everyone else does, otherwise you’ll look poor by comparison.

That said, perhaps when the final Lions/Pencils are being decided, award organisers should check out the reality of certain claims, including the UX, the UI and the actual viewership of that TV news station in an obscure corner of the Balinese archipelago.

Until that happens, it might be worth taking a look at that HBO case study to see where things might or might not be as they seem (I will emphasise here that I have no idea if these were on the level or not. This is just an exercise to show where unscrupulous case study makers might spin things. This is not any kind of suggestion that the HBO Voyeur team was anything less than 100% honest):

00:25: ‘Street teams passing out curious invitations’. We have no idea to what extent this really happened. You can assume that many people who feature in this kind of footage are agency/production company staff. Even if the ‘passing out’ is genuine you might get better takes with more appropriate (cool-looking) ‘passers-by’ when you use agency staff.

00:35: How long was that projection up for? You tend to need permission for these things, so an agency might get some quick footage (again with ‘members of the public’ who might not be members of the public) to suggest this went on for hours. And ‘two high-def projectors’? Weird flex, but OK.

00:45: ‘Viewers could hold up their invitations to discover clues’. Were those clues clever and interesting, or just a nice addition to the film that no one can check on? Impossible to say.

1:10: You can see trailer footage of the stories that makes them look as interesting as possible. Were they actually interesting? Who knows? And anything that ‘airs on TV’ (yeah, HBO is a TV channel) ‘and in cinemas’ (how many times?) is not a big deal.

1:20: The promo drove viewers to the website. How many viewers?

1:25: Then we see the UI working perfectly. We have no idea if it really did that, or if the site crashed, or if this all just happened in the Mac room at the agency.

1:36: ‘We got the coolest musicians to compose original tracks’. No juror would have listened to those tracks. ‘Coolest’ is very subjective, but it sounds great, and nobody is going to check up because ‘cool’ and ‘obscure’ are often synonymous when it comes to music. Would it ‘fit the exact choreography’ of what you were watching? Again, who would be bothered enough to check that?

02:00: ‘Viewers are invited to…’ Did they do it? Did they care? Was the story engaging? Who knows?

02:22: There’s a link from the website to a blog called ‘The Story Gets Deeper’. Again, this all sounds so wonderfully multi-dimensional, particularly in 2008, but no juror would ever have checked that blog to see if it was well written etc.

02:35: More clues and cell phone footage that no one would check, and no one would know if any viewers were interested enough to follow them.

02:45: New York Magazine covered it. We all know how PR works, especially when it isn’t a real article. This is just a mention on their ‘approval matrix’ that might have been placed for a fee or favour (or maybe New York Magazine liked it for real!).

02:50: HBO fans shared their passion for it… in ways that are impossible to verify. How many times was it shared by real people? No idea.

03:00: Over a million unique viewers ‘sought it out’ in the first three weeks. ‘Sought it out’ could of course mean that they just Googled ‘HBO Voyeur’, but that does sound good. Not sure how many people constitue ‘half of all HBO On Demand viewers’. Why not use the stat of all HBO watchers? Were there many HBO On Demand subscribers? And how much HBO Voyeur did they have to watch for it to count as part of the stat?

As I said, all those elements could be as real as they were presented, but as they came from an ad agency, you can be fairly certain that they were at the absolute top end of that reality. Why wouldn’t they be? As I also said, it would be weird not to frame everything as positively as possible.

How have things changed in the ensuing fourteen years? Not much, but let’s have a quick look at this year’s big winner, ‘The Lost Class’:

It is more sophisticated, with great shots and emotional music. They have some genuine big hitters on the news front (MSNBC and CNN, along with pull quotes from Fast Company, The Guardian and Rolling Stone), and that can’t be faked or exaggerated. The only part where it breaks down a little is 1.4 billion impression with zero dollars spent. What exactly is a ‘media impression’? And they clearly spent a bunch of dollars making this and, I would suggest, getting it out on social media. ’66% increase in background checks conversations’? What does that mean and how was it measured?

The big claim is that it started another big gun control conversation without needing another tragedy. That is quite vague. The gun control situation in America is very complicated. Did the NRA double down as revenge for the humiliation of its leader? Did gun fans take offense? Gun tragedies always lead to people buying more guns because they fear theirs will soon be taken away; did this inspire more of that? Post Uvalde we’ve just had a piece of gun legislation finally pass the Senate. Was that aided or impeded by this?

It is undeniable that they made a big, famous splash with a sneaky idea that liberal gun control fans would love (MSNBC, CNN, Fast Company, The Guardian and Rolling Stone could be said to be preaching to the choir. What did The Daily Wire and Fox News think?). Did it move the needle in the right direction? Hard to say, but the case study video did all the right things to bring home many big awards.

So now we have to be case study-vigilant, especially as portfolios are now full of case studies, and the people who hire creatives want to see evidence of big-ass case study-worthy campaigns.

Perhaps we should just accept that the creation of the case study video is a skill in itself, one that every agency now needs to master to have any chance of a a big award. We can all take the claims and stats with a pinch of salt, then marvel at the editing and the use of music, but we should also know that bigger agencies have entire departments that have optimised case study video creation, and have more resources and favours to call in to make them even better. Unfair? Sure, but life isn’t fair.

As someone once said about democracy, case studies are the worst system we have, except for all the others. They are the best medium to explain campaigns that people have never seen, and give societal context for people who may not live in the country where the work ran. But let’s not pretend they are anything other than the sugar dusting on the cherry on the icing on the cake.

We should use our critical thinking to make sure the right questions are being asked about anything dubious, otherwise it’s going to be on us when a piece of work that wasn’t actually very good is held up as an example of the best we can do.

(By the way, 1.65 billion media impressions agree with this post, and it’s going to start at least one conversation between two people standing next to each other in the toilet of an ad agency in Turkmenistan.)

I work in PR. The impressions are utter nonsense.

We fight against this all the time: They will almost always be the domain-level number of monthly impressions for the whole site – not the number of individuals that went to the page the campaign was featured on for the one or two days it was relevant or accessible, let alone how many of them actually read the piece.

We’ve had clients wanting to use 30 million impressions for Yahoo! (based, I would guess, on people having it set as their homepage), when the truth was probably less than 30 thousand.