Newish things that haven’t made advertising better, part 8: scam ads.

On LinkedIn there’s a fella who likes to post ads that have inspired him, offering them to others in the hope that they have the same effect.

Often one of the commenters under the ads is me. I find myself taking issue with the fact that the ads are usually ‘scam’, by which I mean they are created solely for the purpose of entering into awards, and not real answers to real client briefs that are intended to solve actual business problems.

The most recent example of this featured an expansion of our two viewpoints in the comment section, so have a look at both sides of the issue:

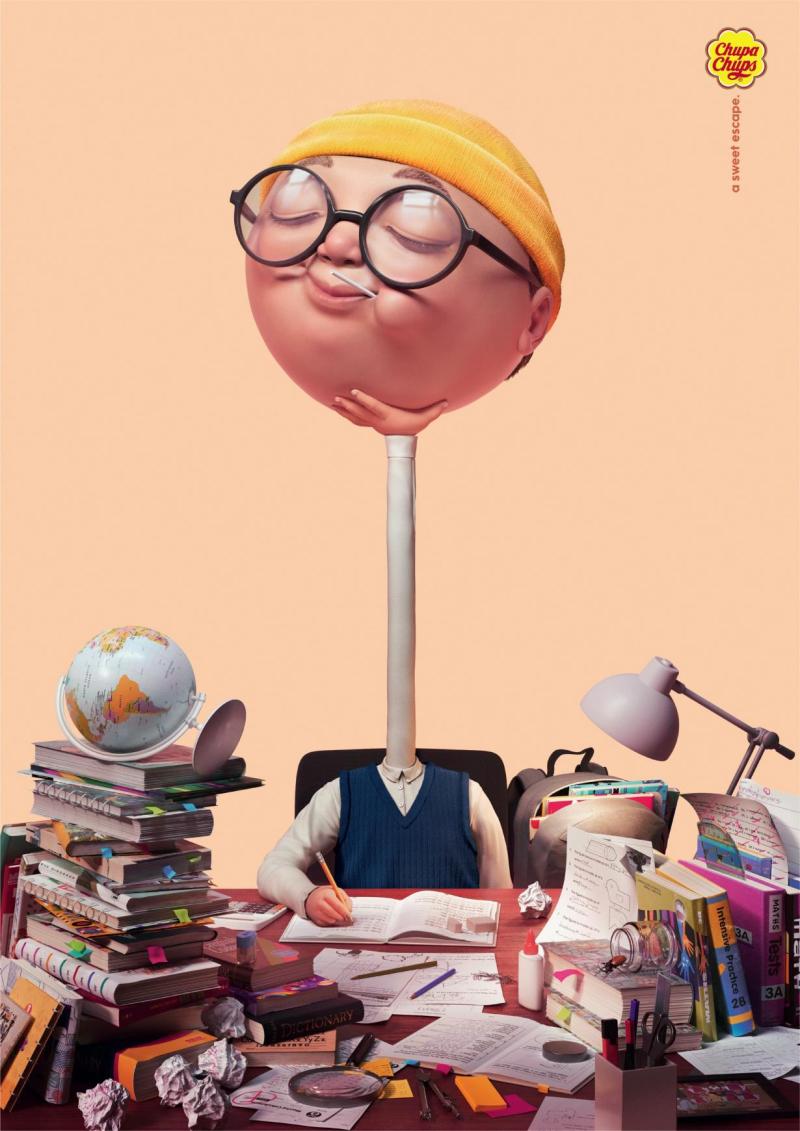

Here’s the ad…

Andy Lockley, ECD of Content at Grey London started things off:

I was doubtful that Chupa Chups actually briefed an ad agency to create a print/poster campaign to promote its lollipops. So I contacted Chupa Chups to ask if this was an actual advertisement that they had created or if it was just ‘fan art’. They confirmed my suspicion that is was the latter. I know you’re a fan of these type of simple visual articulations, but many are nothing more than vanity exercises by ad agencies / ad agency creatives designed to seduce awards juries in one big echo chamber. All a bit tragic really.

To which the original poster (OP) replied:

Think you might be missing the point of my feed Andy. This is about inspiration. I’m trying to expand people’s executional sensibilities. Sharing stuff that catches my eye or in this case visually expresses the feeling of enjoying a lollipop. If this is spec/student work, good for them for executing to this level. Looks better than a lot of real ads I see. Now if your point is that it doesn’t work as an ad…all opinions are welcome but if you are saying it’s doesn’t work as a piece of inspiration, I disagree.

I joined in:

Alas, I think it inspires people to take the path of Cannes scams instead of necessary ads for real clients. This would never sell a lollipop in a million years. But it is a nice illustration 😉

OP replied:

Really? I find inspiration in this and I don’t go on to make scam. I try to take the rails of any typical expected executional paths. It’s like gathering artistic references and looking at modes of expression for use down the line.

Me:

I didn’t say ‘everyone’. I said ‘people’. The celebration of scam breeds scam. Maybe not everyone, maybe not today, but its proliferation has helped bring the industry to its current sorry state. Let’s stop holding it up as anything to be inspired by. It makes us look childish and irresponsible. Beyond that, these ads just aren’t very good.

OP:

It’s advertising Ben. Why so serious? I feel like it’s that ‘tude in particular that’s taken the fun out of this industry. The shit work is based on shit strategy and phoning in the work. Blaming the industry’s faults on this is actually funny.

Me:

Just one of many reasons, which is why I said ‘helped’, not ‘brought’. We can produce good work on good strategies, but no one bothers anymore because they can do bullshit like this. Then you can put it up on LinkedIn, I’ll point out why it’s shit and the wheel keeps spinning. Then we can agree to disagree on who is part of the solution and who is part of the problem.

End scene.

I wanted to put both sides of the argument because I think many people in the industry see scam ads as harmless fun that can be inspiring (this is borne out by the supportive/complimentary comments).

So what’s the problem? Is my ‘tude a bad thing? Let’s go into the origins of scam and see if the answer lies there.

For decades creatives have altered ads for award entries. However, it used to be just the surreptitious removal of an ugly phone number or website from the entry proof. Or the two-minute director’s cut that ran once at 3am on some obscure satellite channel. Cheating? Sure. But the amended executions were based on real ads, and the alteration was relatively small, so they weren’t really getting an unfair advantage so much as presenting an actual answer to a real brief in its best state. Crime-wise it’s more parking ticket than GBH.

Then in the early 2000s awards seemed to take on greater importance. The Gunn Report provided a quantifiable measurement of creative superiority (even though it has never disclosed its methodology) that agencies could use in their pitch decks, or as PR fodder to trumpet how great their year had been. There seemed at last to be a direct financial benefit to the agencies and holding companies that were winning awards.

But we soon found ourselves in a live illustration of Goodhart’s Law: When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. Instead of awards being a consequence of good work, a certain kind of work was being created as a consequence of the benefits of awards.

I’m not saying these are all bad ads (although some, like the Chupa Chups example, certainly are). I’m saying they are not ads at all.

The skill and value of the job is in using some form of communication to solve a business problem on behalf of a product or service. If we’re just making stuff up, we’re not doing that. Why would Hot Wheels use sophisticated, conceptual double page ads to sell their cars to kids who don’t like or understand that kind of thing? Have you ever seen a Tabasco ad in real life that shows some kind of exaggeration of the heat of the sauce? Come to think of it, have you ever seen a Tabasco ad in real life? Or all the award-winning WWF ads? Or Land Rover ‘you can drive anywhere’ executions?

They are like the tree that falls in the wood with only an awards jury to hear it.

But maybe I am just being Mr. Buzzkill, and this is essentially a benign exercise in showing what advertising people can do when all the circumstances are right.

Sorry, no. Here’s why:

- We look silly to clients. Explain to someone who pays for your work that you don’t like what they approved, so instead you’d like them to sign off an award entry for a completely different campaign: “Why?” To win awards. “But can’t you win awards with the campaign you’ve just made for me?” Ummm… It’s not really good enough. “Why not? You said it was the best you could do for me. What am I paying you for?” It’s not like that. There’s a certain kind of ad that wins awards and… “And our campaign isn’t it?” Er… yes. So will you sign off this other campaign so we can enter it and show how great our work for you can be? “Go fuck yourself.”

I once explained this situation to a client. She thought it was pathetic. It is pathetic. - It’s a massive distraction from the real job. If you feel like the campaign you’re working on is never going to get you a Cannes Silver, are you going to spend late nights making it as good as it can be? Not when you can spend agency, time, money and attention on making a fake campaign that might win instead. Here’s the metaphor: you won’t try hard to make your relationship work with that perfectly nice girl/guy because you have a top-end blow-up doll at home, and it’ll let you do anything. All those kinky layouts you’ve always wanted to try! Take your bold ascender and stick it wherever you like! Hubba hubba!

- They give a false impression of what a creative or agency is capable of under real circumstances. Thinking of a cool ad for a long lasting battery while you’re sitting in the pub, then persuading your local corner shop to let you make an ad for Duracell under their name, then calling in all your favours with your photographer friend to make it is not the same as having to answer a brief with a deadline, a budget and a choosy client. The latter requires real skill, and it’s how ad agencies pay their bills, and therefore exist to pay you. If you show your portfolio of scam ads to a prospective ECD, you’re lying about your ability to do the job that will pay your wages. Agencies are lying to clients about their ability to produce brilliant work. People don’t like being lied to. It makes them annoyed. It makes them think the liar is a bad person who doesn’t deserve their generosity and support. In 2019, we all need all the generosity and support we can get.

- It’s not fair on the people who abide by the rules. Are we all running the same race with the same kind of equipment, or are some of us doing our thing on a specially-sprung track using rocket-powered trainers? If your hard-won answer to a real brief is beaten by the agency that closes down in August just to work on that year’s award entries (true story), is that fair? You’ll miss out on raises and promotions because you thought you had a real job and tried to do it properly, you credulous twat. In addition, large agencies have a big advantage when it comes to making scam work: calling in expensive favours, leaning on clients for permission, buying media space etc. (At this point I should mention that I can kind of see why new agencies and young creatives make scam. It gives them a relatively large boost when they’re trying to find their feet, and they’ll often do proactive work to see if they can get some publicity or suck up to a client or boss. But mature creatives and agencies really have no excuse.)

- It leads to the creation of a certain kind of ad. There are cues you could hit to theoretically increase your chances of awards: no copy, logo in the bottom right, overdone visual… but then you’d be shutting yourself off from some real creative thought. It’s Goodhart’s Law again: the measure becomes the target, and suddenly you’re aiming for what gets you a Cannes Lion instead of what gets you an original or effective ad.

So is it inspiring, harmless ‘fun ‘tude’ stuff, or another nail in the coffin of the credibility of an industry whose standing has never been lower?

Cast your vote with your next piece of work.

I, i, i, i, i, i like you very much. I, i, i, i, i, i think you’re grand. You see that when i feel your touch. My heart starts to beat, to beat the weekend.

Newish things that haven’t made advertising better, part 7: complexity.

Advertising is an industry fueled by simplicity. At our best, we create simple messages, via a relatively simple process: work out what a client wants to say, say it persuasively, get that message out to the people they want to hear it. The more we add complexity, the worse our output becomes.

Complexity is difficult to grasp, annoying to process and off-putting to engage with, but for the last twenty years it’s become a more significant element of what we do.

So join me as I slip back through the mists of time, to a gentler, simpler epoch…

When I started off there were generally four media channels: press, posters, TV and radio. (Coming up on the outside were the ‘ambient’ media opportunities, but let’s face it, most of these were awards-fodder bullshit.)

Let’s just think back to that time with a collective ahhhhhhhh…, as if we are now sinking into a soft leather armchair, accompanied by a Whisky Sour and a bowl of kettle chips. Just imagine: if you had to think up an advertising idea, it only had to exist in one of those four forms, two of which were pretty similar to each other.

The work was better then (see all the other posts in this series). That’s not just my opinion, there’s a graph I can never seem to track down (if any of you have it, do send it my way) which has collated many answers to the question, ‘Do you think the ads are better than the TV shows?’. The line starts at a healthy spot in the early nineties, with quite a few people saying yes. Then it starts to head downwards at the kind of pace that would put the shits up Matthias Mayer. Yes, the TV shows have improved, but let’s not kid ourselves: the ads have become worse.

Is that because of complexity alone? Of course not. Budgets, brain-drains, the internet, open-plan offices, the rise of the holding company, globalisation etc. have all played their interconnected parts, but at the root of everything else is the spiraling growth of an overall complexity.

Let’s return to those media channels. With only four, they could, to a certain extent, be mastered. Some of us were informally allowed to specialise still further, with creatives being recognised for their abilities in TV or press, and fed more exclusively with those briefs. But most of us might be handed a poster brief one day, and a radio brief the next, or we’d be asked to come up with a mixed-media campaign that had to work across all four channels.

The advent of ‘digital’ changed all that. like water seeping in under a closed door, the digital briefs started to become more numerous and take on a greater significance. Banners started off as a little joke, where you’d kind of pat them on the head and send them on their plucky way before returning to the real stuff of billboards and TV commercials.

But then they became a more integral part of things, added to many briefs, and not to be sniggered at. In 2007, industry commentators told us that if we didn’t have digital in our book we were in danger of becoming dinosaurs. Places like R/GA demonstrated the need for explaining things like ‘UX’ on lots of whiteboards, and we were certainly not in Kansas anymore.

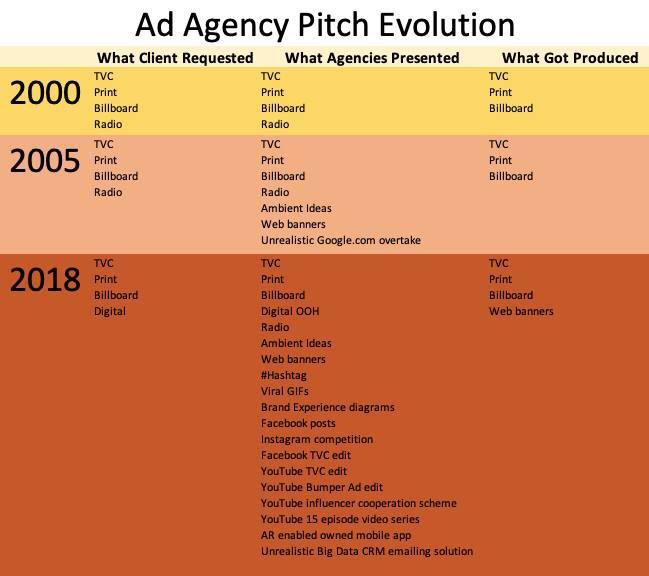

Year after year, digital rose, and with it, complexity. Here’s a chart that sums it up nicely:

To me it seems self-evident that the ability to maintain quality over those 15-20 channels is far harder than doing so over the span of the original four.

Press, posters, TV and radio still need to be fed and watered, so we’re clearly having to spread the same talent and money over a much larger area. Except it’s not the same talent and money, is it? The grind, and the fewer opportunities to produce big, famous work, has put many people off taking up residence in adland, so the talent is of a lower quality. And the fun and games of neo-liberalist capitalism have left the financial side of things… now, what’s the technical term? Oh yes: fucked. A tweet from Saturday should illustrate this neatly:

So there’s less money and less talent, but far more stuff to make.

That situation has complicated staffing. We now have comms planners, digital production, digital strategy, gif makers, social ECDs, CRM experts, search arms of media companies, influencer network advisers, content producers and many more. All paid, on average, less than their counterparts would have been a decade earlier.

And we have more agencies for those jobs. Some big companies have consolidated the new needs into their existing departments, or created new departments, and a bunch more complication. But many new, specialised companies have arrived to cover the new disciplines. And then they have to try to work with each other to span the new varied ‘needs’ of the average client, complicating their own working systems, especially as each was trying to eat each other’s lunch and protect their own.

Adding these layers has taken attention and money away from the ads, which themselves have become more complicated: one ad in one medium keeps an idea simple, but each new medium adds a additional degree of complication in terms of maintaining the integrity of the idea. It may be the case that the new channel expands the depth of a campaign, but it also adds a need for other skills, along with their attendant practitioners, each with a specific set of opinions and agendas. Extra human beings can complicate things at the best of times. These are not the best of times.

Of course, when I said ‘one ad in one medium keeps an idea simple’, that’s much more in theory than in practice. Clients and planners have always struggled to keep to a single-minded proposition, explaining that ‘We’re the fastest safe car in the world’ is single minded, while giving you a withering look of condescension. But when you proliferate that multiplicity over numerous strategists, channels, comms plans and agencies, you vastly increase the potential for complication.

We can say that in India but not in Brazil, so change it. They’ve moved the media budget from CRM to social, so change it. The experiential agency just had a similar idea turned down, so change it. Two planners from the telco hub in Detroit like the idea of ‘conquering fear’, while two others at the media agency in Austin prefer ‘expanding bravery’, so change it, etc.

Mix that lot up, chuck it out all over the place for all sorts of people, and good luck making it simple enough to be effective.

I get that we need to be where the eyeballs are, but the eyeballs are now everywhere, and each location has its own best-use advice. You might think a banner is just a digital location for a poster, but is it rich media? Do you go programmatic or white list? Which shapes and sizes have you bought? Does your line or visual fit all of them? If they’ve just been added to the media mix, have you bought the talent out to a sufficient extent? What are the KPIs? How do you measure them? When will it reach the desired clickthough rate? Is the Shopify UX ready? How do you know if the increased sales came from the banner or the radio ad? Does the smaller additional media budget justify enough production cash to make the ad properly?

And on, and on, and on, through many clients, CDs, creative agencies and media agencies, each with different answers that might change from hour to hour, or even from minute to minute.

And I haven’t even got into the different payment terms, or how HR staff have keep up with the needs of the people required to produce this campaign, but not that one. Maybe you can maintain a flexible, freelance workforce, but do they deserve healthcare, or an invitation to the agency Christmas party? What about their plus ones? What venue do we book if they all say yes? Can the budget stretch to that? If that means sausages instead of prawns, how will that affect the vegans?

See what I mean? Questions on questions on questions, all of which need to be answered, but many of which are tedious, time consuming and expensive, adding further to the complication.

Ernest Hemingway, that stellar practitioner of utter simplicity, once wrote the following exchange:

“How did you go bankrupt?”

“Two ways. Gradually then suddenly.”

And that’s how we found ourselves in a web of complexity more fiendish than a dozen intertwined spider webs.

I have no idea what the solution is, but when we finally come across one, I bet it’s simple.

Like to take a cement fix. Be a standing cinema. Dress my friends up just for show. See them as they really are. Put a peephole in the weekend.

Newish things that haven’t made advertising better, part 6: globalisation.

Back in the 1990s your average D&AD annual was filled with work from British advertising agencies. In fact, it was called British Design and Art Direction. Around this time it also contained a smaller ‘International’ section that gradually became subsumed into the main annual/awards.

So what? It’s just some silly old advertising awards.

Well, that was just one tiny piece of a much larger jigsaw puzzle called globalisation. Feel free to read an absolute shedload about the idea, but the TL/DR is that over the last 30 years, the world has become more centralised and, as a result, homogenised. This has happened in all areas: politics, commerce, art etc., and advertising has certainly been part of the process.

Clearly I’m not going to go into the whole kit and caboodle, but the parts that relate to our industry have been a corrosive shit show. Here’s why…

To start with, let’s go back to those D&AD annuals. They’re a good metaphor for all the other guff.

As a rule, the fewer people an ad talks to, the better. Obviously an ad aimed at a single person will work better than one aimed at a million. You can leverage nuance and cultural reference to greater effect, and your messaging will have no need for the kind of lowest common denominator stuff that turns persuasive messaging into vanilla blancmange.

For example, an ad like this one played well in Britain because it took the piss out of an historical antipathy between England and Germany. Of course you can argue that prising open old wounds to sell beer is irresponsible and damaging, but that’s for another post that I won’t be writing. The 1990s were a different time, and although I don’t want to excuse a kind of low-level racial stereotyping, that ad was a perfect answer to that brief at that moment.

Let’s fast forward to 2019. Of course there are still ads that target national audiences, but they are becoming fewer and further between. Instead we are given briefs for communications intended to be as effective in Singapore as they are in Swindon. Many have to appear online, to be viewed by the multicultural, international audiences of The New York Times, Guardian and Pornhub.

More companies are becoming subsumed into other companies, and those bigger companies tend to sell stuff in multiple markets. They also like to save money by creating one ad that can run in all those markets. They can then claim this aids global brand consistency, which is great, because if you’re in Mongolia and you want to buy a Heineken, you won’t think it’s entirely different from the bottle of piss you bought in Mogadishu.

This leads us to the holding companies. I debated giving them an entire ‘things are worse’ post to themselves, but there’s not that much to say, except that, like all big, homogenous companies, they’re leveraging economies of scale, monopolistic conditions and international reach to achieve to the most cost-effective ways of things.

Is there really any difference between WPP’s Ogilvy, Grey, BunchoflettersY&R and PlaceThatUsedToBe JWT? Maybe you think so if you work there, but the rest of us just think they’re a bunch of agencies that WPP gets to pitch against each other so it doesn’t lose accounts (money).

But back to the ads. In my time working on the worldwide rollout of Apple’s commercials I was asked if the need for language and cultural adaptation would mean that we would be unable to make another Mac vs PC if someone thought of it. I weighed up the extra script writing, production, budget and resources required and replied that the odds would be low. Yes, globalisation means that a campaign named as the best of the 2000s would now be virtually impossible.

Of course, global ads can still be brilliant (including Apple’s). From Independent Litany to Dumb Ways to Die most of the Cannes Grand Prix winners of the last twenty years, could record a new VO and run all over the world. But they are the exception rather than the rule.

The default position tends to be the kind of thing you experience in an airport: dull kaka that uses big, abstract concepts, such as ‘connection’, ‘synergy’ and ‘progress’ to say nothing much at all. That’s what globalisation really means: jack of all bollocks and master of none of the deep, engaging human truths that are an essential element of what we do.

And the awards thing is just a self-fulfilling prophecy. D&AD is simply another version of Cannes, with every member of every jury coming from a different country. So the Croatian copywriter will never understand the power of the Peruvian insight, and the Nigerian ECD will be left non-plussed by the reference to Mrs. Brown’s Boys.

But if you stop awarding the esoteric, you start to encourage the homogenic; ads with no words that can be understood by every juror in every (non) language. And the vicious circle starts to spin even faster: blander work, created for more people, rewarded by juries that have little choice but to pat it on the back, leading to even blander work etc.

Add all that to everything else that has makes 2019 advertising bland and the handcuffs are tightened still further.

We now have a smaller playground to play in, and if you want to ask that kid if he wouldn’t mind pushing you on the swing, you’d better be prepared to ask him in Esperanto.

That girl is a real crowd pleaser (oh yeah). Small world, all her friends know of me (know me). Young bull livin’ like the weekend (ah).

Newish things that haven’t made advertising better, part 5: open plan offices.

Ah… this is like shooting a marlin in a really small barrel using every single weapon Arnold Schwarzenegger has ever looked at.

I’m saying literally every single creative on Planet Earth hates open plan offices.

But it’s Saturday evening, and my kids are on their third rewatch of The Cleveland Show, so let’s do an easy one.

Back in the 1990s every team had an office to work in, and ads were much better. Are those two facts related? Does the Pope shit in the woods? Just imagine… you have some work to do and you can – get this! – close a fucking door while you do it. Amazing! So you have the peace and quiet you need to concentrate on a bit of copy or art direction, but more importantly, you have a sealed-off environment in which to talk about whatever you want.

Now, this is crucial to the creative process. You need to feel comfortable discussing anything, from Barry Lyndon to Barry Sheen; from geometry to geopolitical crises; from Jimmy Krankie to Jimmy Savile. That’s how you get your ideas going, so you need to be able to let it all hang out, and look stupid, tasteless and stroppy, should the mood take you.

Next, you need an office to stick stuff up on the walls. This allows you, and everyone else, to judge your ideas. So you put ’em up, accept the inevitable feedback, and improve your work. It’s like a small, crappy version of the Pixar Braintrust.

You also need an office to house your books, videos, TV for watching inspiring reels (or football), shoot loot and all that junk. You can create an environment in which you feel ready to work, be that minimalist and tidy, or a candidate for a documentary on hoarding.

Last but not least, you need a place to bitch about the other people in the agency. I’m not suggesting for a minute that you should do that gratuitously, but you’re going to have to do it sometimes, because people are dickheads sometimes. Venting helps mitigate any negative feelings you might have about that.

So open plan offices have deprived us of all those good things:

You no longer have a reliably quiet place to work. Yes, you can pop to the local coffee shop/park/toilet, but it’s in no way the same as having a place, stocked with a pile of your most inspiring stuff, that you can call on at any time, where you can get away from the planner who likes shouting about Yuval Noah Harari, or the finance people who discuss their troublesome veins, or the other team who are working on the same brief as you, and would love to take that great idea you’ve just explained to your art director, and make it just a little better before the presentation deadline (true story).

And you now have to discuss the merits of Alien 3 vs Alien 4 in front of people who will then think you’re an indulged prick who just gets to waste time while they do the real work. Even if they don’t say it to your face, you could well imagine a chat in the kitchen that ridicules and trivialises your conversations. (And that doesn’t even include all the people who think you’re an idiot for preferring Alien 4.) The way we work – the way we have to work – is not the way the other departments work. We don’t produce spreadsheets or Effie papers, and if we need to discuss Vic Reeves and American Gladiators to get to a good solution, so be it.

Even worse is when you have to say your shitty ideas in front of people who don’t understand that ‘Woody Allen building his own playground’ is the first step on the way to a business-boosting Cannes winner. You need a safe space to vomit out all the crap from which you can pick out the nuggets of gold. So every glance of derisive incomprehension is another speed bump in a process that is already fucking hard.

That need for safety will extend to the now-non-existent walls of your now-non-existent office. Remember when you had a place to judge six nascent ads alongside each other? Remember when you could ask for a colleague’s trusted opinion on said ads? Remember when you could stick up reference photos next to layouts to see how they hung together? Sure, you can now do all that on a computer screen, and it’s exactly the same. Except it isn’t. That 13-inch Powerbook isn’t an entire wall, so I’m sorry for your loss, but tough shit: the global headquarters of your holding company needed to prop up the Q3 earnings call by saving some cash, and fitting more employees into a smaller space was an easy win, so deal with it, you wanky prima donna.

And where do you keep all your stuff? In the pedestal, obviously! Cram a few David LaChapelle books in there, along with all your (literal) bottom-drawer ideas, a Magic 8-Ball and that money bank in the shape of the cat out of My Neighbour Totoro. Is all that stuff necessary to writing a good ad? Define ‘necessary’. Pixar thinks having your own space is essential, but what do they know, eh? They made Cars 3, so they can piss right off (they also made Toy Story 1-4, Inside Out, Wall-E and all those so-called ‘classics’, but: Cars 3).

Creativity is a fragile process, so poking holes in it, tweaking its nipples, and farting in its face is not recommended. Maybe a favourite set of poker dice will never be the difference between brilliance and excrement, but that kind of stuff can’t be measured, so within reason you should give creative people the environment they need to succeed. Ot at least, don’t entirely ruin that process by giving them 22 inches of white desk in a room as noisy as the third row of a Selena Gomez concert.

The last compromise, the one about venting and bitching, is probably the smallest, mainly because that kind of thing is better done in the pub or coffee shop. But sometimes you just have to get in a vaguely sound-proofed room, shut the door and swear a lot. It helps because it’s therapeutic and gets you back into the game more quickly. Sometimes it can lead to another idea that replaces the one your ECD just killed, and it helps if that happens in your working environment.

One more deadly thing about OPOs: headphones.

In the days of offices, no one wore headphones, so everyone was open for business at all times. You didn’t have to lean over them creepily until they noticed you, or tap them on the shoulder and hope they weren’t too startled. The dynamic was different: spontaneity was possible because you could just chuck stuff out and know someone was listening. Today you have to enter another situation called ‘sorry to disturb you’. It’s a different transaction, where you’re figuratively knocking on your partner’s door, with no idea what’s taking up their attention. So what you’re showing them had better be worth the disturbance. And you’d better not do that six times in five minutes, like you might do in an office. Each interruption must be earned, and that’s a broken, stilted path to creativity.

Maybe all of the above makes sense; maybe a mere 3% is of merit. But it matters not. My shoddy opinions can be disregarded in favour of the many scientific studies that shit all over OPOs. Nothing suggests they are better than the alternative. they are officially nothing but a money-saving exercise that has contributed to the worsening of our output. They are a post-vindaloo toilet blockage. A short-term gain for a long-term pain in the arse.

Unfortunately, I don’t think they’re going anywhere soon, but until they leave our professional lives we’re going to have to accept that we’re working with one hand tied behind our backs, and a vociferous, candid member of the comms planning department yelling about his favourite podcast right next to our ears.

Wondering in the night what were the chances we’d be sharing love before the night was through. Something in your eyes was the weekend.

Newish things that haven’t made advertising better, part 4: The perpetually open office.

Back in the 1990s ad agency Fridays had a different vibe about them: people would come in at some point, often with a hangover from an elongated and inebriated Thursday, pretend to do some work until the earliest point at which they could reasonably head off to lunch. Then they didn’t really come back. Or they came back to an office that was almost empty, with any stragglers possibly just hanging around because they were in town and meeting friends nearby in the evening.

Yes: for most of us 1990s creatives Friday wasn’t an actual work day. I believe the same applied to the 1980s, but on a grander scale, with even less adherence to the notion of punctuality. (Gray Jolliffe, great creative and subsequent inventor of Wicked Willie, was once stopped by his managing director when sauntering into the office late in the morning. “Hey, you should have been here at 9 o’clock!” said the manager. “Why?” replied Gray. “What happened?”).

And it wasn’t just Fridays. Sometimes a slow Tuesday afternoon adjourned to the Carpenters, the Crown and Two or the Prince of Wales, where ‘work’ stopped, fizzy chat started and the world was put to rights. (I should probably add that this early exit wasn’t entirely confined to drinking situations; people might also have popped to the cinema, an art gallery, Selfridges, Comme Des Garcons, the Eurostar to Paris, or even home to spend a few more hours with their families. Crazy, I know!)

So the informal 4-day-week was an assumed thing. I think it still exists to some degree today, as staff are often allowed to leave the office a little earlier to beat the weekend traffic. But here’s the question: in 2019 do they ever really leave the office?

Email, Slack, shareable Google Docs and Keynotes, Workplace Chat, text messages, Whatsapp etc… As someone wiser than me once pointed out, you’re now in the meeting that never ends, during the 24/7 workdayweek.

Just for clarity I’d like to point out that there’s nothing wrong with working hard. And under the right circumstances (a good, well-organised brief in service of a decent product would be a start) long hours can be also be fine. I’d also say that most of the industry would gladly welcome the 8 hours x 5 days arrangement, as is amusingly suggested in their contract, with voluntary extra time on top.

So whether you’re checking your emails, ‘just’ taking that ‘quick’ call on holiday at the expense of spending time with the people who deserve your attention, or adding another ‘late one’ or weekend to your week’s tally, the job never really ends.

I’ve written before about how enough extra hours will eventually add up to another half-a-member-of-staff per year, per team – an additional employee that your company gets for free under the guise of ‘work hard, play hard’ or some such bollocks. Anyone who works long hours that aren’t their own ambitious choice is doing so because their bosses took on extra work without having to pay extra people to do it, and that’s a big expense off the books.

A friend of mine once took a job on the express understanding that he was going to do a real four day week (not a lazy Friday situation as described above) for 80% of his regular pay so that he could complete other projects he had taken on. To me, that would create a weird tear in the space-time continuum, where some part of the week was actually ringfenced to be entirely out of bounds to the account teams and project managers that simply can’t cope without 168 weekly hours of you. Sure enough, the ‘just this quick one’ messages started coming in on Friday mornings and spreading throughout the day because this deadline was close, or that director call couldn’t be missed. In the end he was simply doing his normal job for a 20% pay cut because trying to keep those emails and Slack notifications at bay is like being King Canute, sitting on his throne in front of an ever-encroaching tide.

And the really sad thing is you probably don’t even notice it. It’s now the water you swim in. The way things are. The status quo. And so it goes for 2019 lawyers, journalists, publishers, doctors and almost any job that’s eventually supposed to lead to decent pay and enough status to allow control of your own schedule.

But here’s the real kicker: that day will never come.

In fact, the higher you rise, the more demanding things get. So you’ll almost certainly be at the beck and call of some opportunity, client, or ’emergency’ to the end of your working days. Yes, it might be easier at the top because you can occasionally just walk out when you really need to, but I recall speaking to an old ECD of mine telling me that he literally remembers nothing of his youngest son over a particularly onerous two-year stretch.

When my first kid started to crawl it was mentally demanding: if I happened to turn around for a moment, when I turned back he could easily be on the other side of the room. So all I could really concentrate on was where Jackson was and whether that location was dangerous. And because we were new parents, both my wife and I took this task on. After a month or two I came up with an idea: I would take on the job for two hours, then my wife would take the next two. That meant that instead of being 90% on alert for four hours, we could be 100% for two, and 0% for the other two. The effect was amazing: we could actually read the paper, watch TV, go for walk or get some work done for a couple of hours. And even the babysitting time was better because we knew what our job was. Instead of being half-distracted and panicky, we could go to the playground and enjoy proper time with our son.

Long story, I know, but you can see where I’m going with it: when you perpetually have something going on in the background, whether it’s the need to answer an email, or the threat of the need to answer an email, or the possibility of an ‘important’ massage arriving just as you’re settling into a long-awaited date night or movie, or the possibility that the weekend plan you’re about to make will be upended by a last-minute pitch (and, by the way, the better you are at your job, the more ‘indispensable’ you become, so your reward for excellence is the extension and expansion of the nightmare. Hooray!), you can’t concentrate on or enjoy anything else. It’s like someone tapping you on the shoulder all fucking day; a kind of mental water torture. No wonder we lose people to other industries.

And no wonder the work is getting worse. It’s simple maths: if you preoccupy people on a constant basis, you give them no time to feed their minds with anything that might be useful to the creative process. And you give their subconscious no room to make all those little backroom combinations that bring forth creative solutions. And you add stress and bother to their days, increasing cortisol, which messes with brain functions including the all-important memory, which I believe is useful for helping people to remember stuff, and that might then be useful for having creative ideas.

And what are the benefits? Always being available to make sure someone can answer all those questions and make those adjustments that are so crucial to the success of a project? Again, we can always measure quantity, so you know the number of hours, emails, phone calls and meetings someone has attended, but there’s no way of clearly assessing the content of those interactions. Were they all successful? Were they all beneficial? Were all of them necessary? Were any of them necessary?

Which brings me back to the 1990s: no email, no text messages (except the Nokia 3310 ones that used punctuation to make it look like popping a bottle of champagne), far fewer meetings, no Slack, no shared docs but (altogether now)…

Somehow the work was better.

Archives