A Convenient Truth

Back in the day, listening to music wasn’t easy.

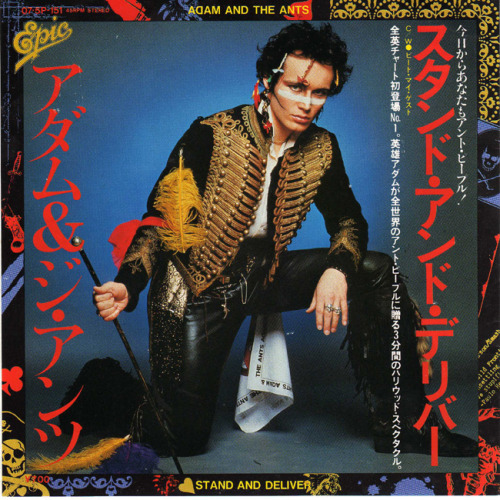

Either you waited for it to appear on a radio station at the same time you happened to be listening, or you bought it, which back then was quite an expensive undertaking. I got into music as a kid in the 1980s so a fiver or tenner for an album was a lot of money. Hard decisions had to be made between the relative merits of Adam and the Ants and Culture Club.

And heaven forbid if you had heard of a something brilliant and American that hadn’t been released in the UK. If you were lucky, you could find it on ‘import’ but then it might cost three or four times the regular price.

All of that meant listening to music was not a convenient process, but it also meant I appreciated it far more. Maybe the opposite of ‘easy come, easy go’ is ‘difficult come, difficult go’, where anything you’ve worked hard to obtain gains value through being elusive.

scarcity=elusiveness=value=appreciation=happiness

Whereas

ubiquity=convenience=whatevs

But ubiquity and ‘convenience’ is where music is today. It might seem counterintuitive, but having every song in the universe in a box in your pocket has some cons to go with the pros.

Last week I downloaded the new Chidlish Gambino album. I love several of his older tracks, so as it was basically free (Apple Music) and convenient (one push of that little cloud icon), I would surely just pipe it into my ears ASAP, wouldn’t I?

Alas, I have yet to play a single note. I’m not very busy right now, so you’d think I could find an hour to give it a spin, but I just don’t care enough. It’s too ‘on a plate’. I actually prefer to get a vinyl LP off the shelf, walk over to the record player, and listen to music that way, one side at a time. Why? I don’t know for sure, but something makes me appreciate the solid object in the big, beautiful sleeve, along with the warm crackle that follows the lowering of the needle. It’s not convenient, but that’s what makes it better.

And it’s the same with movies. I like to drive twenty minutes to my favourite cinema, park the car, spend quite a lot of money on popcorn and tickets., and sit in the dark with a bunch of strangers. Yes, I could wait for the far more convenient $3.99 iTunes option, but it’s not the same. My way is somehow all the better for being more expensive, more time consuming, and much harder work.

Which brings me to advertising. In the vaguely old days, before about 2002, there was only one way to see ads: in their natural habitat of press, posters and TV channels. These all seemed kind of prestigious, as they were out of the reach of members of the public. The media seemed special, so that made the ads seem kind of special, too.

If you saw a TV ad you liked, you’d have to hope to catch it again by accident, like a song on the radio, before it disappeared completely. And it was that temporary, moment-in-time dynamic, where you either caught it or missed it, that also gave it some of the scarcity value mentioned above.

And where are we now? Ads appear for little cost on your social media feed, to be viewed forever at your convenience, at the size of a playing card, alongside people’s holiday snaps and cat videos.

We now have online previews of Superbowl ads during the week before the game, and Best Ads On TV and The Drum might be the first place you see that expensive new John Lewis ad, played on your phone as you’re walking from the tube station to the office, trying to avoid the dog poo and the traffic.

Yes, it’s convenient: it’s everywhere, it’s free and it’s endlessly repeatable. But it’s also ‘easy come, easy go’.

Sure, in the world we’ve now created, it would be perverse to return to ‘inconvenient’ viewing. But it’s worth considering how we often sell our own work short. For better or worse we’ve all been hard-wired to look down on cheap, easy things, dismissing and forgetting them in an instant. Yes, it costs less to reach many more people in the blink of an eye, but everyone knows that, so there’s little difference between your ad and some kid unwrapping presents on YouTube.

We’ve willingly dragged something elusive down to the level of any old thing, and that’s now how much of advertising comes across. The public doesn’t respect what we do because we don’t either.

The funny thing is, we’re supposed to be experts in communication. Why, then, do we seem to be so unaware of the ways in which we practice that discipline so poorly?

Like you I’m from the time when buying and listening to vinyl was precious and exceptional. The parallel you’re making with advertising is extremely interesting.

Just to confirm your observations, Rough Trade has launched a turntable diary. You upload a 200 words story about the music you listen to and a picture of your record collection. I also uploaded my picture on my IN Lcathlaz.

Interesting.

Thanks!

So I feel like we should be listening to albums together as we watch commercials that repeat the same messaging. I did take pictures and video of the new covid commercials as they aired, especially the “we’re with you alone”, “hands free safe delivery” etc. It was wild and strange to see. Now I’m getting ready to enter the skincare white label world and disrupt that with no repeat. Same. Same. Same….needs to end.