I’ve Started A Free Ad School!

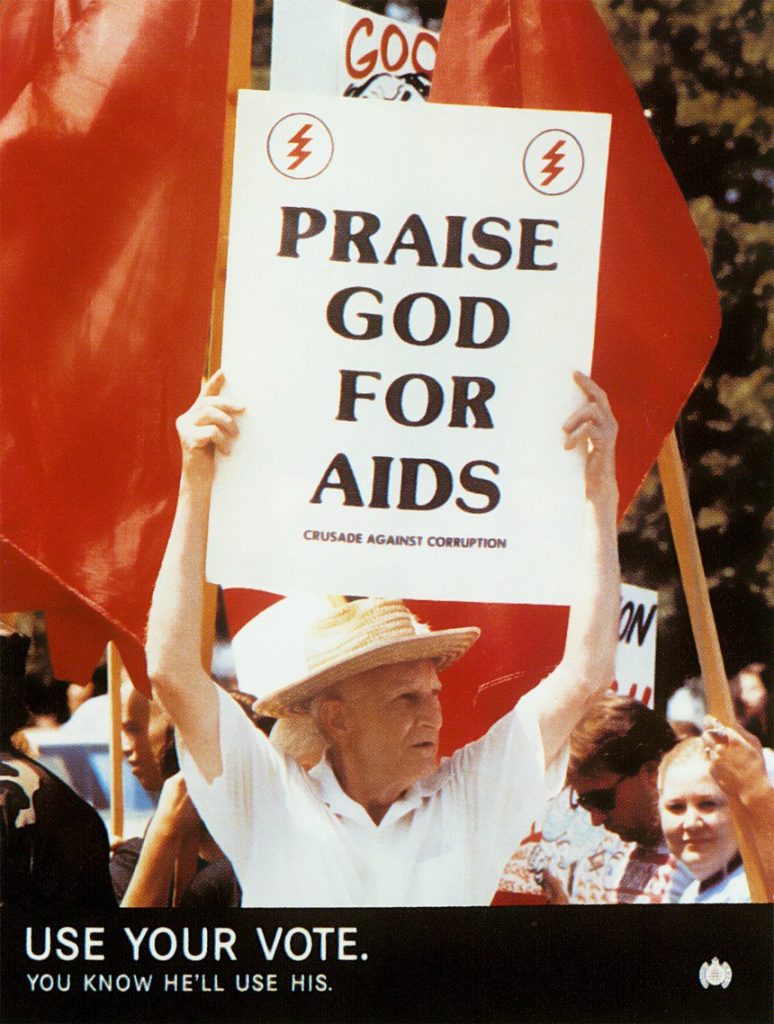

The other day this guy started appearing on my TikTok feed. He was explaining how to make great advertising, and the things he was saying made a lot of sense. So I looked him up and it turns out he’s called Jason Bagley and he’s made some amazing ads and has now started some kind of ad school. Here’s his introductory video:

Jason explains the format in this article: The first class, Creative Megamachine, will run for eight weeks. There will be two hour-long Zooms with Bagley each week—one being a lecture of sorts, and the other being a group discussion and Q&A.”So it’ll be between about 20 hours with me in a pretty small group over Zoom,” he says. “I’m hoping to be the Obi-Wan Kenobi to their Luke Skywalker.” Sounds great, but I can’t find how much it costs and don’t want to sign up for his emails, but let’s assume it’s not free.

The other other day this article (£/$) appeared in my daily Creative Review email. For those of you without a CR subscription, it is a profile of The Barn, a kind of Watford 2.0 based inside BBH London where aspiring creatives actually get paid to learn. The article then goes into why that is a better solution to creative advertising education than the current, relatively expensive options: “I think the ad school model is now being questioned and challenged, particularly if it costs a lot for those students to attend,” he (Tony Cullingham) says, “because, hey, it’s a big surprise – you get rich, privileged students on courses that charge 15 grand a year.”

True.

So those are two of the current options for aspiring creatives, neither of which existed when I was starting out. A third option would be somewhere like SCA in London, or Miami Ad School, which run for various lengths of time, but cost a fair bit of money. I’m not exactly sure where places like Bucks or St Martins fit in these days, but I assume they’re similar to SCA, but perhaps for a smaller fee.

If you want to be a copywriter or art director, I think those are your ‘formal’ education choices, but I wonder what I’d do if I were starting out today, and by extension, what would I suggest to someone who wanted to go down that path.

I’ve written about advertising education before, but more for the benefit of people who are already in the industry but want to improve (something that might apply to the School of Astonishing Pursuits). However, call me deluded, but I still think you could go from a standing start to a job in good agency within a year, and for an outlay of £0, and in such a way that you could manage it around your current annoying job (the one you want to leave so you can work in advertising).

So, welcome to your first day at Ben’s Free In Your Spare Time Get A Great Job Within A Year Ad School.

Here’s the schedule:

- Listen to the podcasts. Fucking hell! They’re free! There are loads of them and they cost nothing. Nothing! Start with Dave Dye’s because they really get into the whole story of how people got into the business and he writes a post to go with each interview that is insanely detailed. Then have a look around at others such as Tagline, or even mine (I occasionally wrote a post to go with my chats, AND I spent five hours interviewing Dave Dye, so you won’t find that on his feed). There are probably others, but I assume you’re resourceful enough to find them. If you aren’t, give up now.

- Have a look at the Archive section of D&AD’s website. If a half-decent ad happened over the last thirty years, it’s there for you to look at and learn from FOR FREE. They’ve recently added the ‘shortlisted’ stuff, so the amount is large and the scope is wide. You could start with the Black Pencils and work your way down.

- Once you’ve done a month of that (or a day of it if you’re feeling inspired) have a go at coming up with some ads. It’s fun. No one can stop you writing whatever you want for whatever client you want. Now, I know I said the whole thing was free, but I assumed, like almost everyone on planet earth, you own a smartphone and can afford a pad of paper. That will allow you to do everything I’ve suggested so far. You can even take a pen from your local betting shop and write ads on receipts, or bits of newspaper that you’ve fished out of a bin. Or unused loo roll from the local swimming pool. What I’m saying is, there’s lots of free stuff around to write on.

- As an addendum to stage 3, find a partner as quickly as possible. If you like writing or are good at it (or both), find an art director, and vice versa. This will increase your chances of getting that great job by a factor of 10000000. Where do you find this partner? OK, I’m not going to do everything for you, but ask around. Advertising is a small business. Explain your predicament to headhunters, go for crits (see below) and ask people you meet there, go to advertising talks… It might take a while, but you’ll find someone eventually, and anyway, the longer it takes, the better you’ll be when you find someone, and the more inclined they’ll be to work with you.

- As another addendum to 3, set yourself a daily quota. Say… one campaign a day. That might mean you produce something shit, but a) The very process of forcing yourself to meet this quota will make you do creative things and b) If you come up with 300 campaigns in 300 days, ten of them will be good enough to put in your portfolio. And don’t stop there. The people who will do best on this course will set themselves a quota of two campaigns a day, or three. Or four (you get the idea).

- Crits. Start calling up/emailing creative teams in ad agencies. Start with the ones whose work you admire most. Tell them why you like their stuff. Do not fake it and do not lie. People love to know that people give a shit about the fact that they exist. Exploit that for your own ends. Find teams in agencies you like and admire. Nowadays you could even try an email crit with a team in another part of the world, then get a job there. This is about gaining knowledge, honing your craft via expert advice and (CRUCIALLY) making friends in the industry who can help you get that job. Aim high. There was a team whose work I loved. I saw them when I was shit, saw them again when I was a bit better, then saw them a third time when they loved my book and recommended it to the ECD of their agency, which happened to be AMV BBDO. Next week I was there on placement. Six months later I had a job at the best agency in the world. That’s why you do you crits. Did I mention they’re not only free, nice creative will give you pens and pads and other contacts in other agencies, which might be the ones that give you that brilliant job.

- Repeat the above until you have a job. The harder you work, the sooner it’ll happen. The less of an arsehole you are, the sooner it’ll happen, so be nice and grateful and humble because people like to have nice, grateful, humble people around.

The course starts in exactly fifty-three seconds and can last anywhere between a few months and the rest of your life, depending on how closely you follow the above, and how much of an arsehole you are. But it’s basically foolproof, so get on with it.

Finally, if you have any problems with how the course is run, you can have a full refund at any time. Good luck!