How all the Nicey-Nicey ads came to dominate the awards.

Last week I wrote that post about how 85% of the Cannes Grands Prix were awarded to for-good/purpose-based/public service/charity initiatives. Then I chucked it up on LinkedIn and received a comment that made the penny drop:

Richard Russell (one of the geniuses behind Honda Grrr) said, ‘Sobering, Ben. But I doubt there are too many in the industry front line that are especially bothered. Yes, it’s rampant now, but I am amused at how we were saying pretty much the same thing in the 80s when Brignull, Abbott, Fink, Singh, etc were scooping all the big UK awards with charity ads. ‘But it’s much easier to win the big gongs with a charity ad’, everyone bleated. And they were right. Then and now. Can’t see that changing much.’

To which, after a bit of back-and-forth, I replied ‘I think this has been a sneaky way of adding the award benefits of ‘charity’ stuff to the difficulty of corporate stuff. Yes, it’s an ad for Mars, or whatever, but now it’s all about saving whales.’

This phenomenon appears to be simply the latest in the timeline of how to game Cannes:

We started with Do your normal day job of trying to sell stuff, enter the best stuff and see if it wins.

Next was Do your normal day job of trying to sell stuff, but when you send the proof in, trim off the ugly things the client wanted, such as the phone number or the address of the local dealership.

Following that was the director’s cut era: Do your normal day job, but however good the 60” or the 30” might have been, get a nice 120” to run once at a friendly cinema, or at 3am on an obscure TV channel. Then you have your epic award entry in its most wonderful form.

Then, as the worm turned with people in the C-Suite taking the Gunn Report seriously for pitch creds, so we then had Do your normal day job, but also deliberately create of ads just for awards. We all remember the ads that were pulled after clients saw them in award books but had never approved them, or ads for clients the agency didn’t even have. But in general it was agencies deliberately taking time off from the day job to specifically create the award ads.

This was exacerbated by the new need for case study videos. No matter how small or insignificant your ‘ad’, you now need to wang on about it for two minutes, usually throwing in some added bullshit for good measure: ‘Sales increased 300%!’ Yes, they went all the way from two to eight. And what is a media impression, anyway? And who counts 1.2 billion of them?

Finally we have where we are today: Do your day job, but either make it a charity ad that is supposedly a non-charity ad, or just do a charity/non-charity ad on the side of your day job.

I’m sure everyone reading this is aware that it’s much easier to to make a charity ad that people care about than it is to make a washing powder ad that people care about. Dying children or disappearing rainforests are obviously much more interesting and persuasive topics than what temperature gets your socks whiter than white.

Back in the day (not that long ago, I think) Cannes did not allow charity ads to win Grands Prix. That, incidentally, is why my old boss, Peter Souter, did not get the biggest of all prizes, despite making this all-time great ad:

Charity vs not-charity was thought to be unfair, so charity ads were in their own ‘product’ slot, but could not get higher than a Gold. But then they added Glass Lions and White Pencils and the whole ‘For Good’ section of Cannes, along with Titanium, which, judging by this year’s winner, also allows charity entries.

At some point during all this, some bright spark twigged that you can turn a corporate ad into a charity ad just by creating/paying for an initiative that might be somewhat related to the corporation, but also (see this year’s Sheba Grand Prix winner) might not.

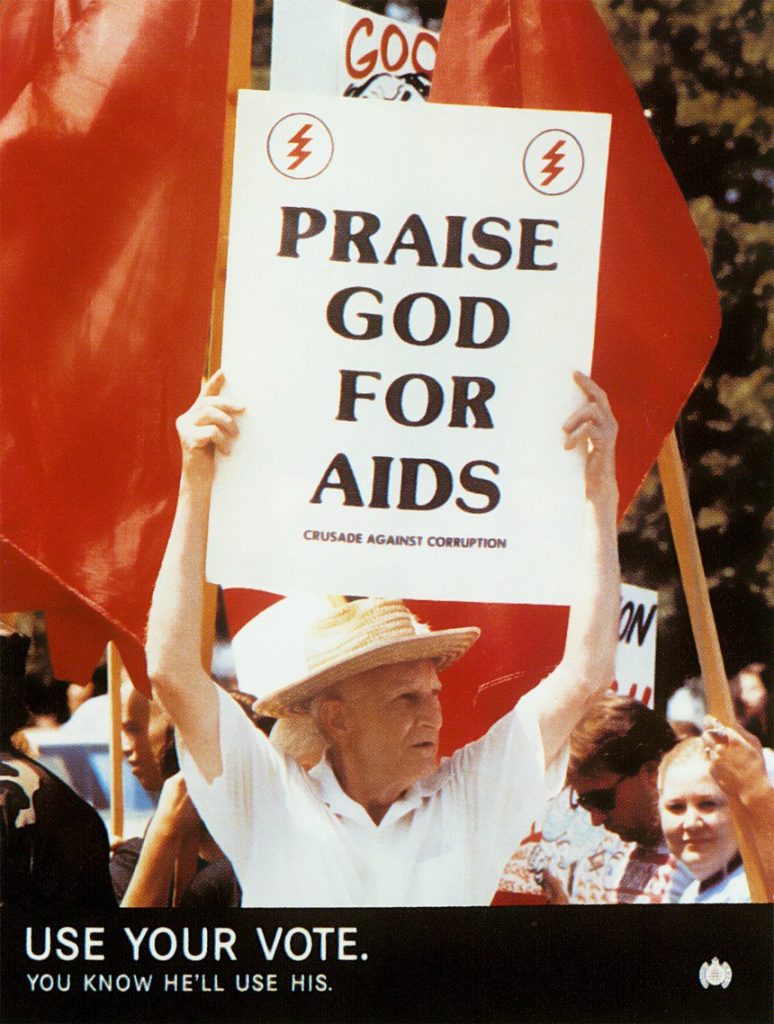

Actually, as I think about it, even this little twist is not new. Back in 1996, the great Flintham and Macleod produced this excellent campaign to get people to vote:

Who was the client? That’s right: late-nineties nightclub du jour, the Ministry of Sound. I guess someone there cared a lot about voting.

But now everything seems to require that little ‘for good’ bit extra. I’ve been involved in a couple of pitches over the last twelve months and I’ve noticed that the client’s brief includes the criteria upon which the agencies will be judged. It says something like ’20% Strategy, 30% Chemistry, 50% Creative’. So that’s what ad award judging is now. They’d like to see 20% Originality, 30% Concept, 20% Craft and 30% Doing Something Nice No Matter How Much Of A Load Of Old Bollocks It Might Be.

The phrase that springs to mind is the tail wagging the dog, but it goes in both directions: juries like charity stuff, so let’s turn our corporate ads into charity ads, which then in turn get awarded by juries, so next year let’s make more of them… and the cycle continues.

I put together the following lists by looking up all the winners of the last decade then wrote down the ones I could still remember. Here are the corporate + Nice winners: Like A Girl, Womb Stories, Dumb Ways To Die, Palau Pledge, Fearless Girl, Mouldy Whopper, Meet The Superhumans, Sweetie, Lifepaint, Meet Graham, We’re The Superhumans, Boost Your Voice, The Talk, Trash Isles, Dream Crazy, New York Times (kind of fits in both lists, I think), The Tampon Book, This Is America and Courage Is Beautiful (man, Dove have been playing this card all along, haven’t they?).

On the Not Nice side we have: It’s A Tide Ad, Magic Of Flying Billboard, Epic Split, Shot On iPhone, Nothing Beats A Londoner, Next Exit McDonald’s, Whopper Detour, New York Times (kind of fits in both lists, I think), Wendy’s Keep Fortnite Fresh and You Can’t Stop Us.

(By the way: if you can be arsed to take a look back at the big winners from the last ten years you’ll see just how many of these Best of the Best awardees have faded into obscurity. It makes very clear just how ephemeral this whole enterprise really is.)

(By the way part 2: I should really make clear that Nice ads aren’t a bad thing as such. Plenty (Meet The Superhumans etc.) are both utterly brilliant and solve a real-life client brief. The problem is the fact that this is starting become unofficially mandatory, whether that was the intention or not.)

So are we going to have to divide awards into Nice and Not Nice in future? If it seemed unfair for the washing powders to have to go up against the starving gorillas in the past, isn’t that the case now? And isn’t that especially so since this is just a little icing on the cake of what the industry really spends its time doing?

The vast majority of ads are still ads, going about their business trying to get people to do part with their time and money for the benefit of some corporation’s bottom line. If we spend our time and attention on the Nice stuff on the side, then reward that as The Best We Can Do, then how will that make us feel about the real ads? They’ll just become a tedious interruption to our efforts to clean up the Pacific, or get senators to vote for Climate Crisis policies, or shame racists into being less racist. All noble aims, but it’s like giving the Premier League title to the team with the most Goal Of The Month winners. Defending a cross, breaking up an attack and passing to the left wing are also valuable skills.

So I’ll just put a little flag in the sand here on the 5th of July 2022 and hope I’ve just got my knickers into too much of a twist. Maybe I’m overstating the significance of a temporary fashion. Maybe the importance of the horse and pony shows that are advertising awards is not actually that big a deal. Maybe the giant glacier of Not Nice advertising will grind along regardless of who is having an angst party on top of it.

One last note on this subject that will hopefully save me having to write a whole other post: could we please just cheer the fuck up for a bit? Life’s a bit of a grind already without turning the entire industry into a ‘who can wear the least comfortable hair shirt’ contest. Even if you’re doing the Nice stuff, maybe do it with a smile, eh?

I think you’re exactly right about everything here, and I’m personally sick of trying to make ads that explain why Product X will make them better, more self-actualized human beings who are doing good for the world. Most things don’t, and don’t need to try to do that.

Hi Ben, I think getting your knickers in a twist is all part of the fun when faced with the crazy hubris of the awards business. I loved this piece and realised that way back when, we would have done almost anything to win BIG. Actually, scratch ‘almost’. Awards = pay rises/promotion/better briefs/being listened to and all that, and maybe that still applies today. But our ‘make the logo smaller’ approach is dwarfed by the sheer chutzpah of ideas like the Grand Prix catnip of Sheba. So far removed from product and brand relevance that it seems not to matter (the contemporary version of a drumming gorilla perhaps?). No one in the real world ever really saw the award-winning ads we used to make either.

While 98% of the agency is selling shit there will always be people looking at ways to turn it into shinola. Ephemeral as you say, but isn’t all of it ephemeral when you step outside the bubble?

Sure, and many would say, ‘If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em’.

The downside of doing that seems small and remote, while the upside might be another 10k in your next salary review.

Great article Ben. So true.