Crap is more difficult than good.

Around ten years ago I was freelancing for a company that wanted some headlines for the apps it was offering on its website. On the face of it the task was simple: take the theme of the app, find some kind of angle, then encapsulate that angle in a short headline.

But the task was actually too easy, which made it difficult.

Let me explain…

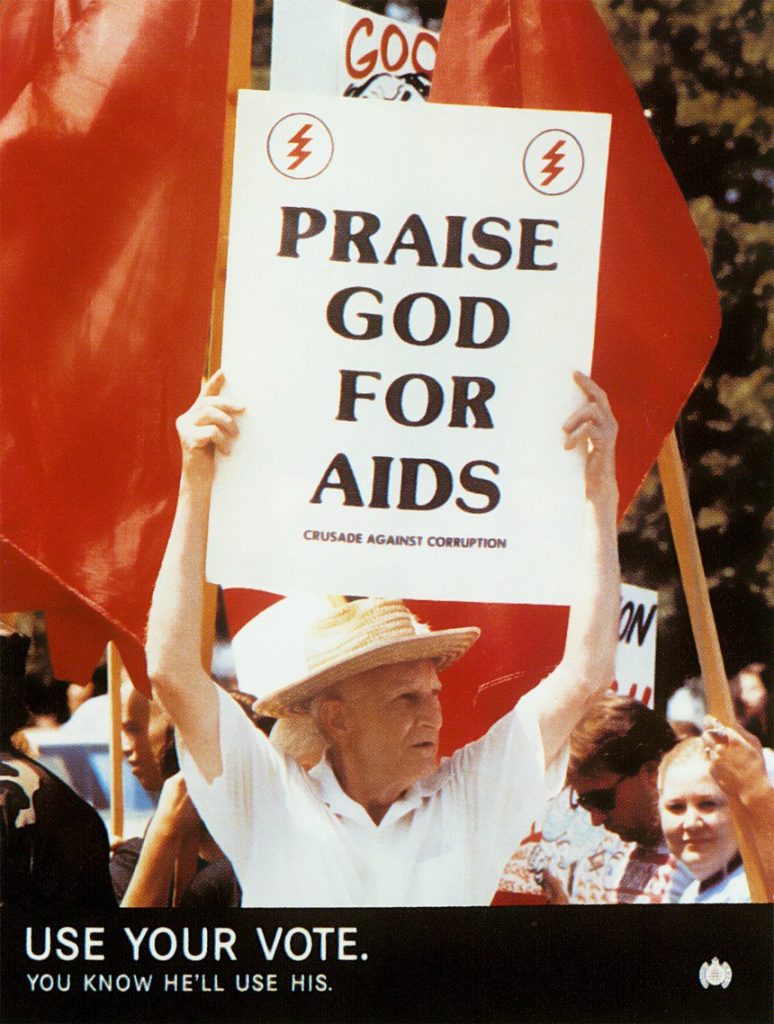

When I was an advertising nipper, I worked at the agency that produced the Economist poster campaign. In addition, the creative department sported about ten of the contributors to D&AD’s The Copy Book (basically the global copywriting Hall Of Fame). So what I’m saying is, the bar was high. In my first month I was asked to write a line for a small space ad for a push-up bra. I can’t remember how many I had to come up with before one was approved, but it was a lot, and the same went for Snickers, Sainsbury’s, The RSPCA and every other client that entrusted their advertising to AMV BBDO.

So I was never asked to write anything crap, and if I had done so, I would have faced the scorn or (worse) the disappointment of my CD. Of course I came up with plenty of rubbish, but it usually stayed on my ‘working out’ page, the one that eventually ended up in the bin.

Cut to ten years later: I’m working on this app brief and doing my best to crank out AMV-level headlines. Once I had managed to reach a standard I might refer to as B minus Economist, I turned them in and waited for the feedback. Alas, on this occasion, I was told that my lines were too good. I must have looked puzzled because the CD then gave me an example of what he was looking for: ‘This one’s about pianos,” he said. “How about ‘Tickle The Ivories’?”.

Riiiiiight.

Now I was really confused. That’s just straightforward. And boring. And not good. But it was also what my temporary boss wanted, so I couldn’t give him my ‘good’ stuff as that would simply be rejected. I had to give him some crappy lines, but that was much easier said than done. How crap would be crap enough? How would I know? Where would I find these lines? I had been trained to write to a certain standard; maybe not quite to the level of The Copy Book, but definitely not ‘Tickle The Ivories’.

So I had a think, tried some more straightforward stuff, got maybe half right and ended that gig soon after. I then had a long stint of full time employment where I wasn’t asked to do that kind of thing, but in more recent years the same kind of request has occasionally popped up again, and I’m still lost.

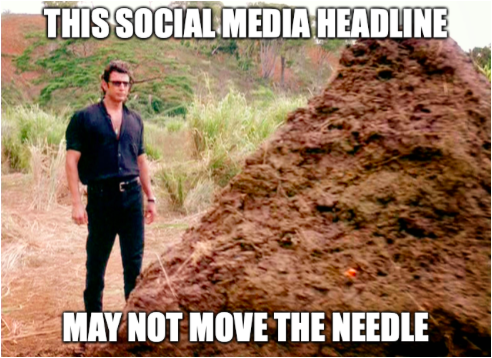

I sometimes end up as the writer on the social media side of things and every time it happens I go back to trying to write ‘proper’ headlines with an idea, or a bit of wordplay; something that might adhere more firmly to the reader’s mind; something that might communicate a lot in as few words as possible. Then I discover that the CD wants a line like, ‘Find a Brighter Tomorrow’ or ‘Make sure you enjoy nothing but the best’, and I try to stop my face doing this:

I have a good go, but I’m just guessing at what kind of crap is the right kind for the brief. I have no idea if I’m hitting the right notes or playing the piano with a Wellington boot. So I get frustrated notes back from the CD, who doesn’t understand why I don’t understand. I really want to give each one what they need, but it can feel as if I’m learning a new language, one whose words are the exact opposite of the ones I’d been taught.

When CDs explain where my crappy lines have gone wrong, I take their advice with a nod and a smile, but it still leaves me none the wiser. How do you know if something is 3/10 or 4/10 (which in their mind is a 7 or 8)?

Let me be clear: I am not looking down my nose at this work, nor the people who want it – I understand that not every brief is seeking an Economist poster, circa 2003. But the general principle of trying to catch people’s attention and hold a piece of it until they decide to buy something in the category seems to be off the table. We are in blah blah land, and I have no compass. They are paying me, so I want to offer a good return on that payment (and I want the bloody task to come to an end), so there is no point in sticking to my highfalutin principles. I just have to give it my best worst shot.

Sometimes these tasks are the entire job; sometimes they’re just a small part of a larger whole, but they tend to be where my involvement comes to an end. To be good at that thing I’d have to retrain myself entirely, but the problem is that most places still want the ‘good’ work, so it’s like trying to ride two horses at once: a feisty thoroughbred and a flea-bitten old mare, bound for the glue factory.

Anyway, First World Problems and all that…

For anyone who pays my day rate but still wants rubbish, I hope I’m getting better at being worse. If I can master the art of the underwhelming headline I’ll save myself and some of my temporary bosses (and their clients) a lot of frustration. But before that happens I’ll always show them something better, then if they still want the turd, that’s up to them.