We Can’t Change Culture Like We Used To

When I worked at Media Arts Lab we had some sort of statement of intent about the advertisng we produced on behalf of Apple. I can’t recall the exact wording but one element of it was the promise that our work would aspire to change culture. And much of Apple’s advertising did just that: from Mac vs PC to Silhouettes to Shot On iPhone, that was what MAL and Apple aimed for on every brief.

It was ambitious, sure, but why aim lower? Advertising has spent much of its modern existence holding its own against the other stuff that has sought our attention. There are many American examples, such as Yo Quiero Taco Bell and The Pepsi Challenge, while the UK changed the public’s behaviour through many John Webster characters, GGT endlines and number one singles from Levi’s ads.

We still manage it now, with the aformentioned Shot On iPhone and the annual announcement of a new John Lewis Christmas ad, but the culture-shifters seem to be fewer and further between.

Which makes sense. Back in Webster’s day there was not nearly as much competition for our attention, so advertising made up a much larger slice of what might interest us. In the UK there were just four TV channels, so whatever happened on them was a much bigger deal, and more likely to be seen by a larger proportion of the public.

Now we have everything from Facebook to TikTok competing for our attention, not to mention old favourites like books, music and films. Despite being able to exist alongside most other interesting things, advertising now feels more fragmented, and thus smaller and less significant than it used to. That means our ability to influence culture has been reduced.

You could say that we had it easy in the past, with less competition for eyeballs, but maybe the fact that we were all affected by advertising made creatives feel that cultural significance was both possible and what we should aim for. I recall a friend of mine writing a Tango ad with a silly action in it, with the express intention of getting kids to copy it in playgrounds. And I remember trying to create my own John Webster ad, featuring a cartoon dog. Both of us fell sadly short.

I’m not saying we don’t attempt that anymore; in fact this new McDonald’s commercial could achieve that very aim:

But I also think that one of the reasons it’s getting so much positive coverage from the online ad community is because of how unusual something like this has become. Office workers may well spend the next six months raising their eyebrows at each other, but that’ll be a rare moment of cultural influence for our industry.

The reasons why this has happened are obvious, but I’ll explain anyway:

In 2008, social media began its inexorable rise. That accelerated the expansion of digital advertising, which is a personal experience rather than a mass media one. If your work is shown mainly in the privacy of a phone or laptop, and no one knows if they’re seeing the same ads as anyone else, your ability to impact culture with that work becomes virtually non-existent.

The second thing it did was give a platform to millions more members of the public. Whether alone or via a Twitter pile-on, the voice of the public suddenly became much louder and more immediate, giving rise to what some call ‘cancel culture’. I think this increased chance of a problematically negative reaction made us retreat into our shells. Far safer to crank out a chest-beating-but-bland manifesto, or inoffensive dance-based ad. They may not have the impact, but at least they won’t require an apologetic tweet from the CEO.

The other thing about culture is that it’s a two-way street: it both influences and responds to the rest of life, so for the last fifteen years, advertising and the rest of public communication has had to read the room before working out what to say, and, alas, that room has been grim.

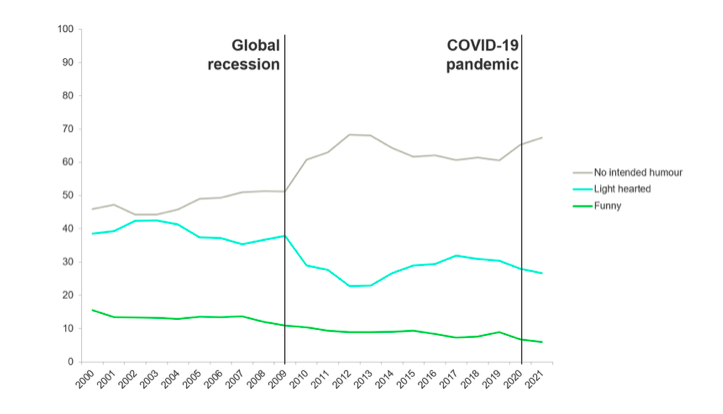

Here’s an interesting article on that very subject. It analyses the reduction in the number of funny ads that have appeared in the last fifteen years.

We’ve all noticed that situation, but this graph…

…clearly shows that it blew up in response to something specific, by which I mean the 2008 crash. Fascinatingly, although a decade and a half has passed since then, the funnies have yet to return.

As far as the UK goes, you could look at the societal conditions of 2008-2023 and concede that things have not improved: the governmental response to the crash was austerity, which has yet to end; Brexit followed, with the public either being sad that they lost or, oddly, angry that they won (possibly because they didn’t really ‘win’ anything, other than perhaps a xenophobic foot-shooting exercise that continues to this day); four years of Trump was stressful for most people across the world; the Climate Crisis reached a tipping point of depressing acceptance; there was that little pandemic thing; Liz Truss crashed the economy; fuel prices have risen; inflation looks like it’ll take us into a recession; everyone seems to be on strike.

Phew!

Worrying about the future has become the default mind state for much of the public, so it makes sense that funny ads have taken a back seat: the ad industry looked around and decided that pratfalls and one-liners might have seemed like turning up at a funeral in a clown car.

Could lighthearted ads have lifted the mood? Perhaps, but instead we entered the heartwarming, laugh-free John Lewisification of advertising. I’m generalising a touch, but overall, the serious 60-second tear-jerker rose to prominence as the 30-second yukfest took a back seat.

In addition, the empowerment of Channel 4’s Paralympics work, Nike’s Nothing Beats A Londoner and Sport England’s This Girl Can was brilliant, but not funny (yes, there were kind of funny moments, but ‘funny’ is not the first adjective you would use to describe those ads, or Womb Stories, or The Last Photo), and we all know about the millions of ever-so-serious purpose-based initiatives.

I would argue that serious ads are, on average, less impactful. They require and elicit less obvious reactions, so a communal spread of approval can’t be kicked off with laughter. Instead we all sit with our own private version of being impressed, so the overall effect is always going to be smaller. Sure, that didn’t stop John Lewis changing the entire industry, but using one example to draw a conclusion about something enormous doesn’t really hold water.

So here we are: a smaller fish in a bigger, more complicated pond, surrounded by negative news coming at us through a firehose. Our response has been a little like what happens when you keep getting hit in the face: confusion, wondering what you did wrong, and working out how to avoid it happening again, when in truth you’re dealing with a brand new set of circumstances that has upturned most of what you thought you knew.

The digital revolution has impacted all of us in so many unforeseen ways, but the difference it has made to mass culture is the one that has changed advertising the most. We may have more sophisticated tools at our disposal, but they haven’t allowed us to better at our jobs.

Then again, that doesn’t mean that doesn’t mean improvement is impossible. That truncated period of change might have given us the illusion that the difficulties of the current circumstances are here to stay. In reality, the extent to which that is true is up to us.