Macarena has a boyfriend named Vitorino’s last name. That the boy swears in the flag swear. He gave it to the weekend.

If I was a sculptor, but then again, no. Or a man who makes potions in the weekend.

ITIAPTWC EPISODE 66 PART 2 – PAUL ROTHWELL

The second part of my chat with Paul.

iTunes link, Soundcloud link, direct play button:

ITIAPTWC Episode 66 Part 1 – Paul Rothwell

Paul would be far too modes to say this, but if you watched a brilliant ad from the late 1990s to the early 2010s, there’s a decent chance he had something to do with it.

As one of the founders of Gorgeous (2.0 – Chris Palmer had already been running a pre-Paul Gorgeous for a few years before he asked Frank Budgen and Paul to join him), he oversaw a peerless run of commercial brilliance that took in Cannes Grands Prix (plural), dozens of D&AD Pencils and a couple of DGA awards.

By 2009 Gorgeous had the unique distinction of having topped the Gunn Report Consolidated League Table of Most Awarded Commercials Production Company in The World every single year since the awards’ inception (1999-2009).

And in 2012 Gorgeous, now 15 years old, was ranked as the Most Awarded Commercials Production Company of the last 50 years, by D&AD.

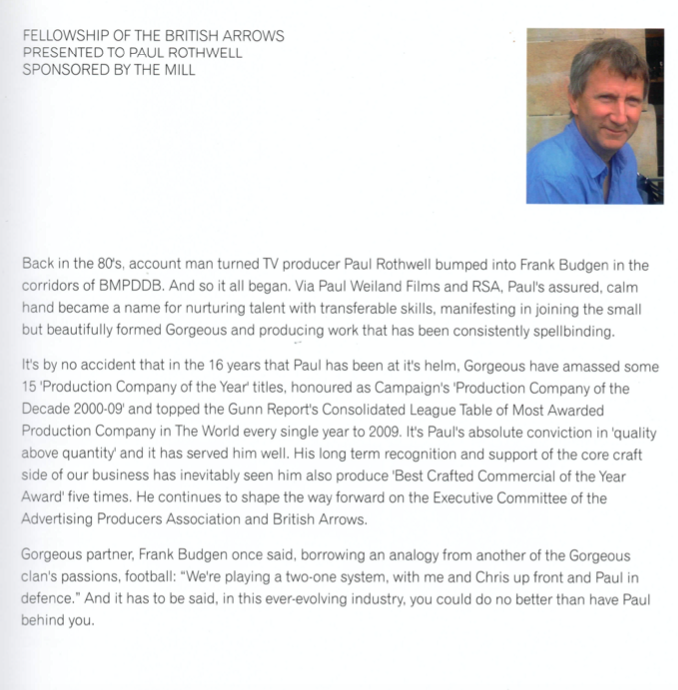

Paul was also awarded the Fellowship of The British Arrows:

But they also made the ads the we all loved, admired, and made many of us want to get into the business.

We discuss all that, along with his earlier years producing on the agency side at BMP, where he first met Frank, and his time with Frank at The Paul Weiland Film Company, and a year running RSA, where he took on Chris Cunningham.

There was so much to discuss, we had to do it in two parts: the years up to Gorgeous, then the Gorgeous years.

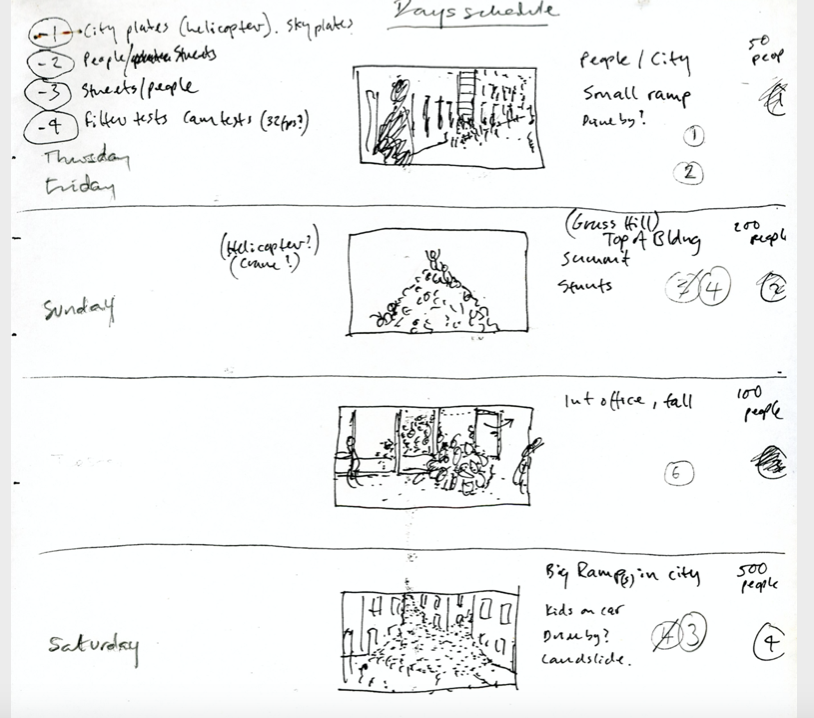

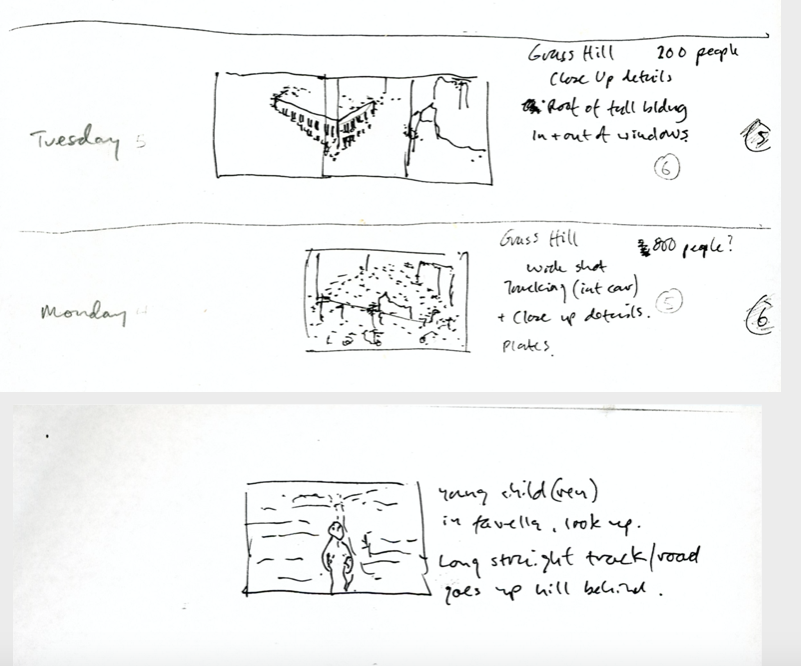

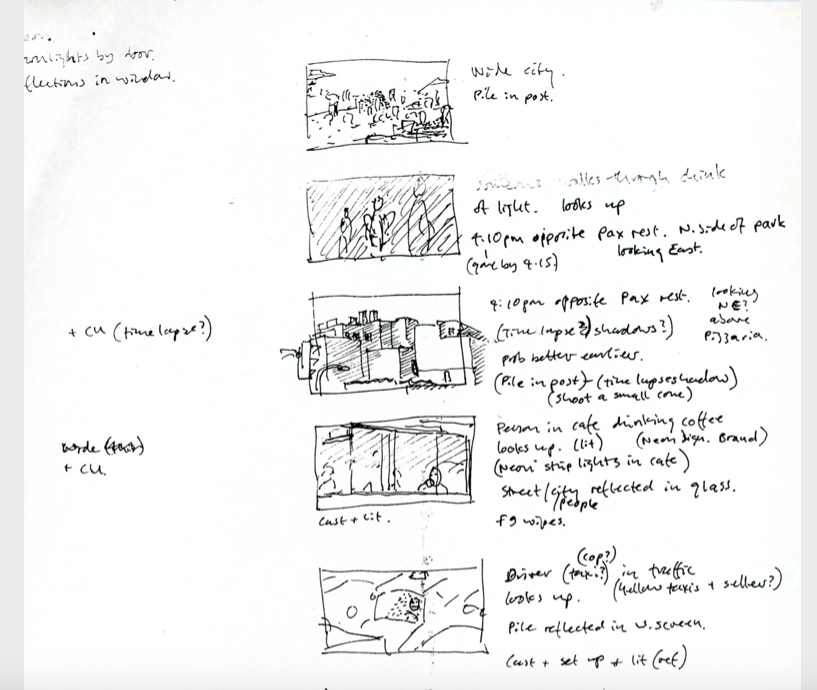

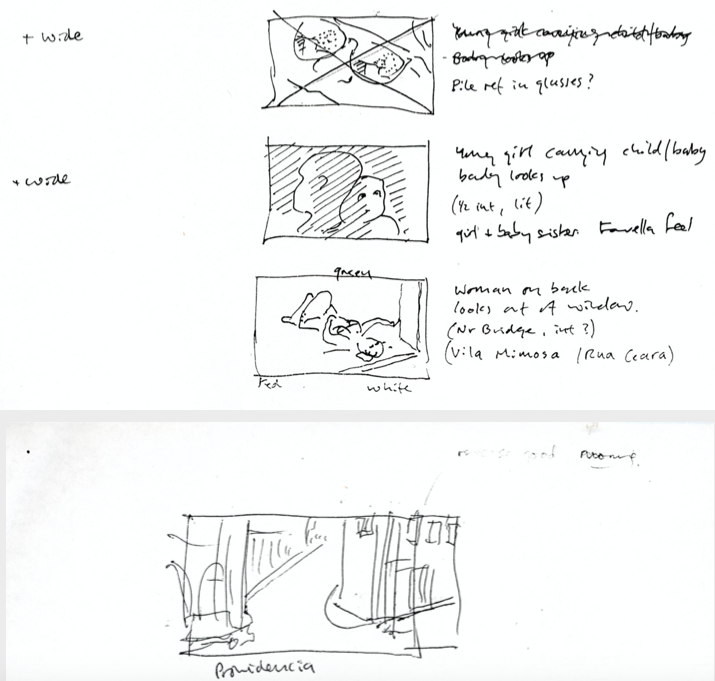

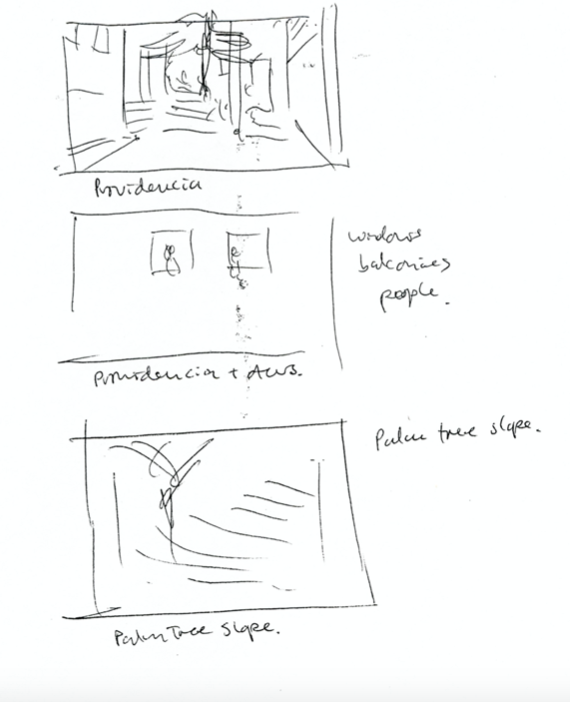

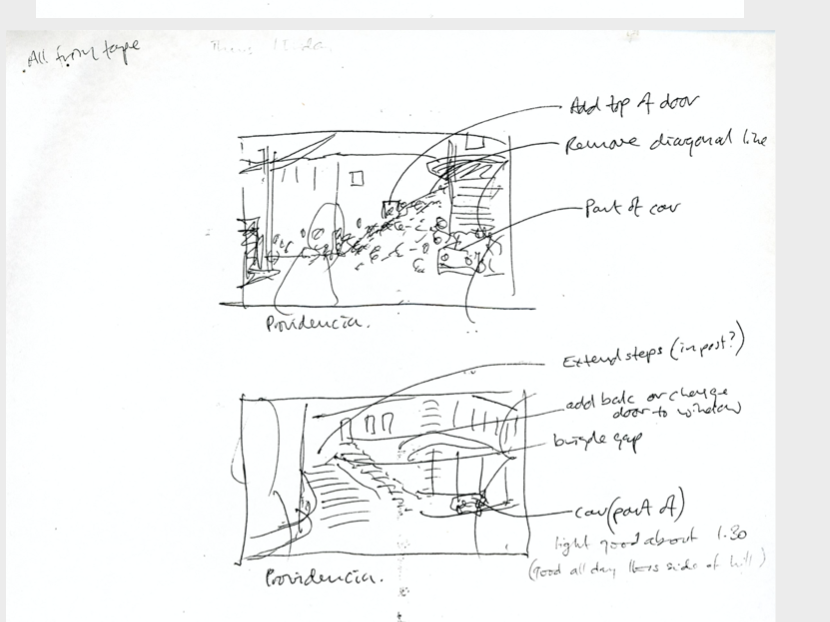

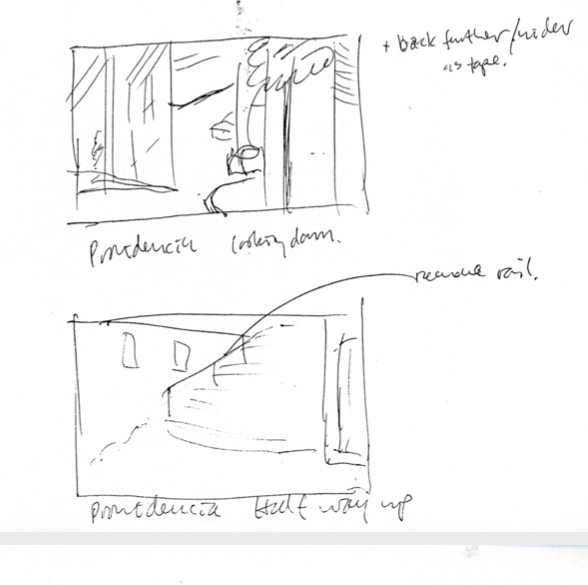

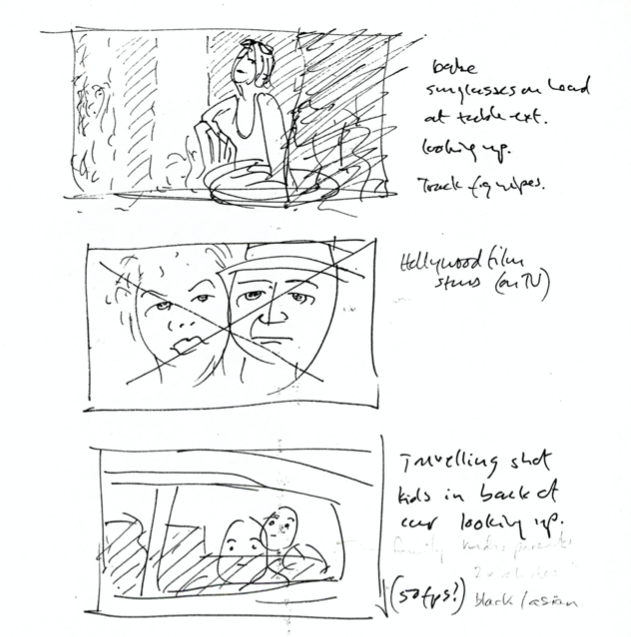

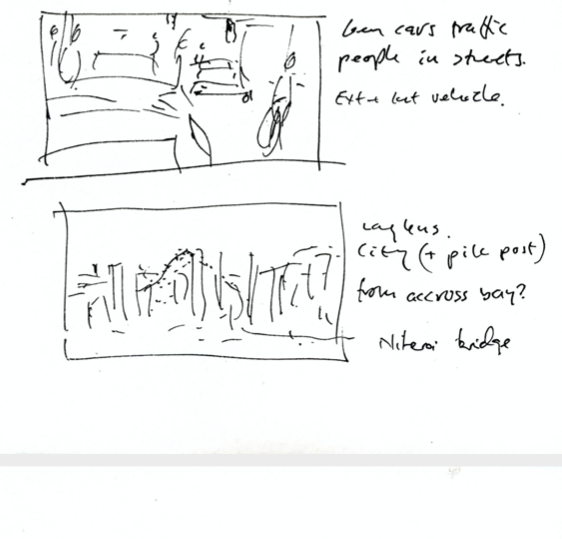

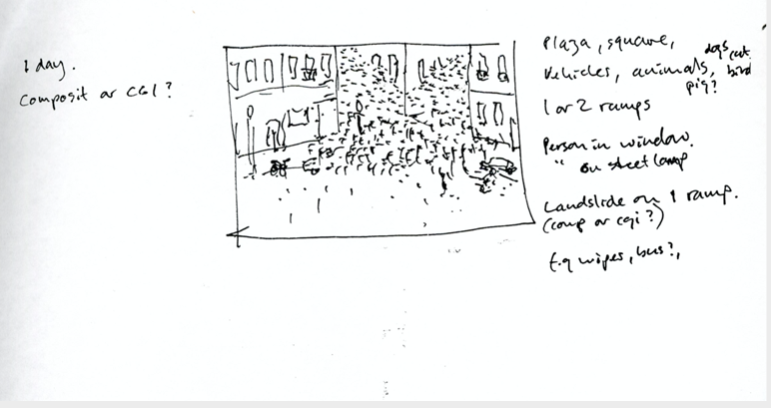

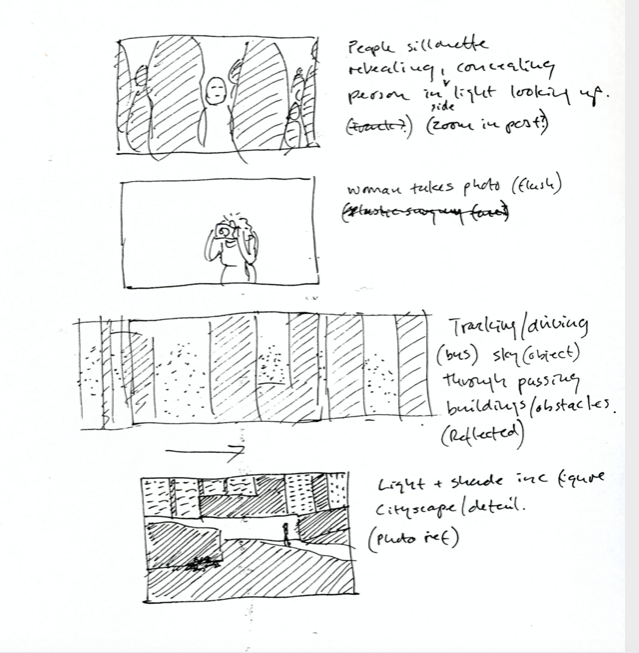

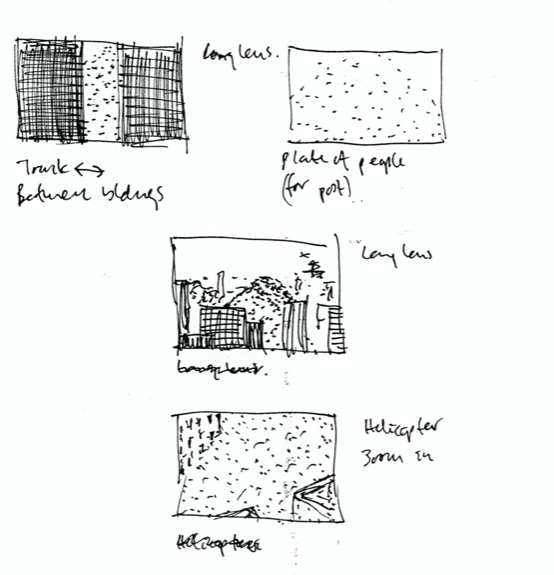

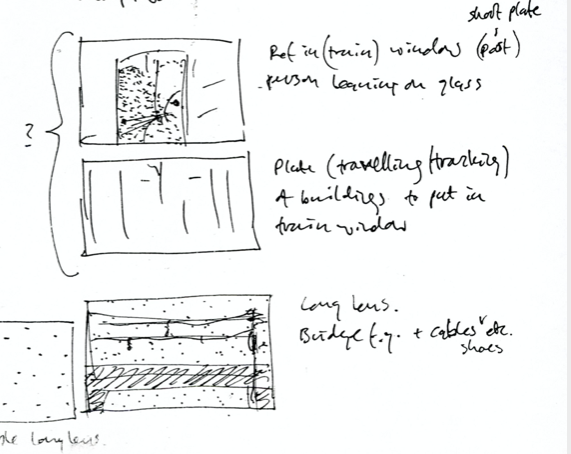

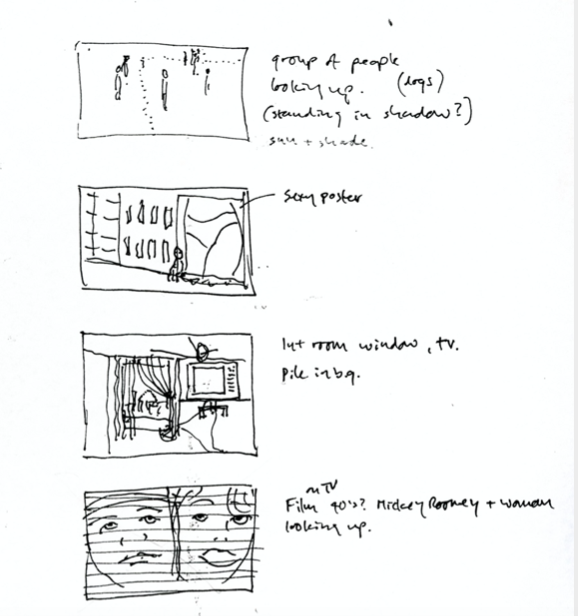

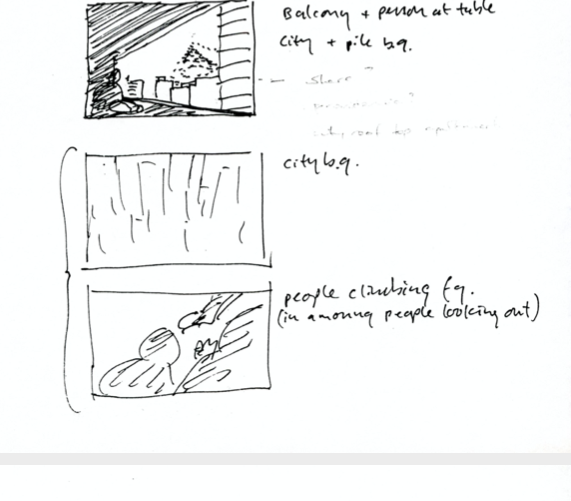

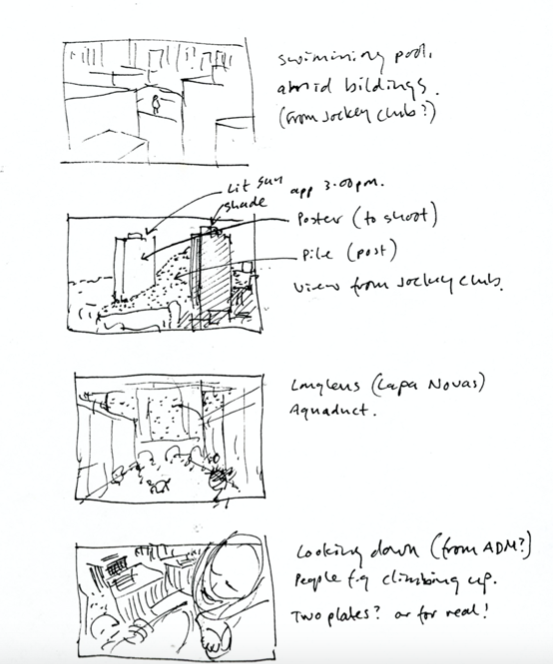

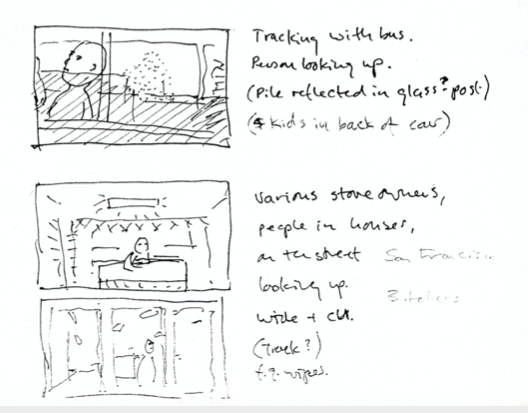

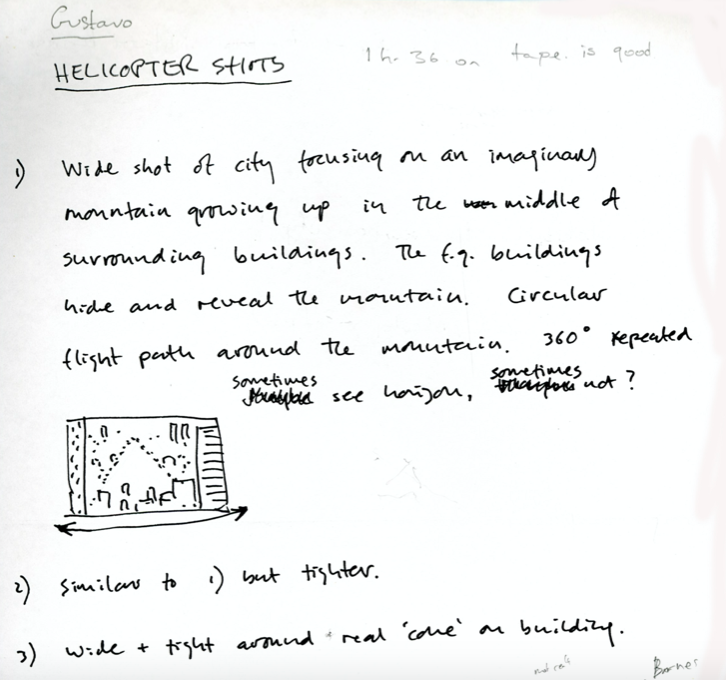

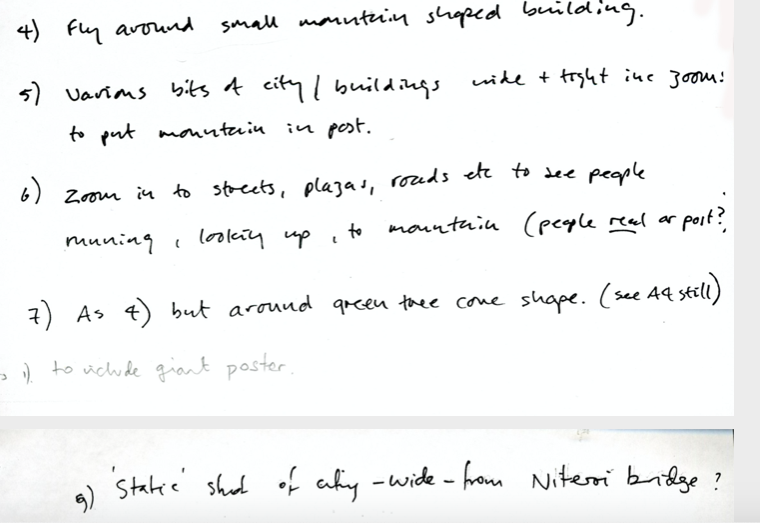

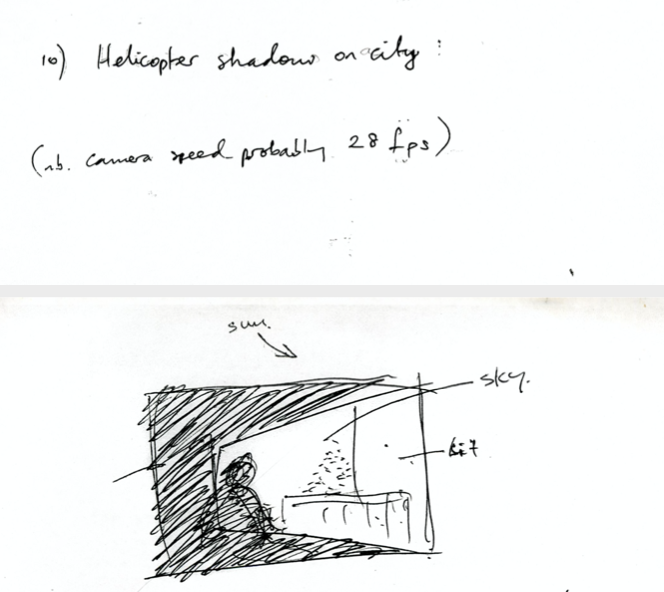

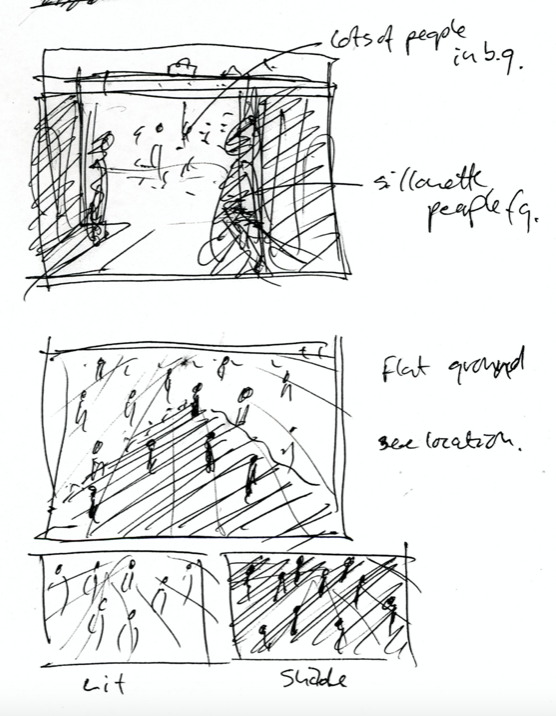

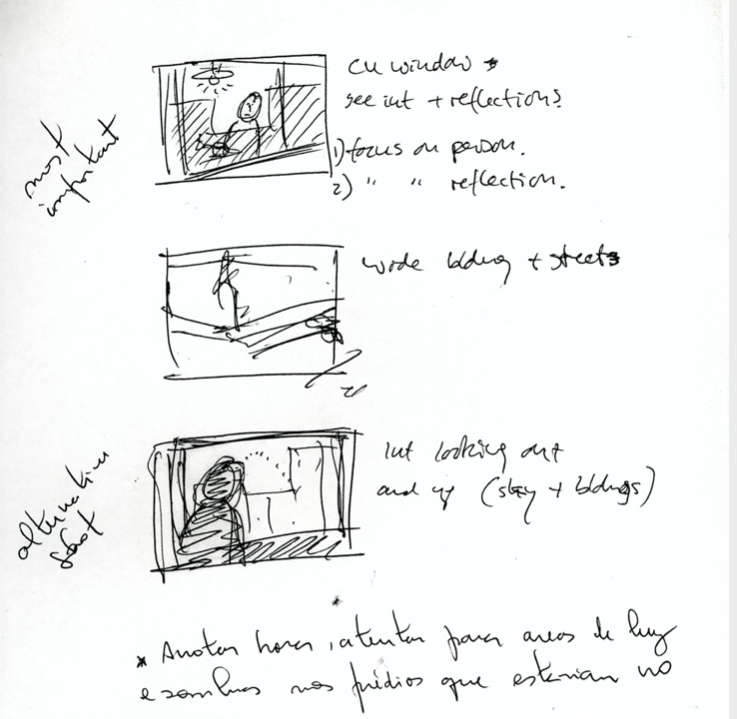

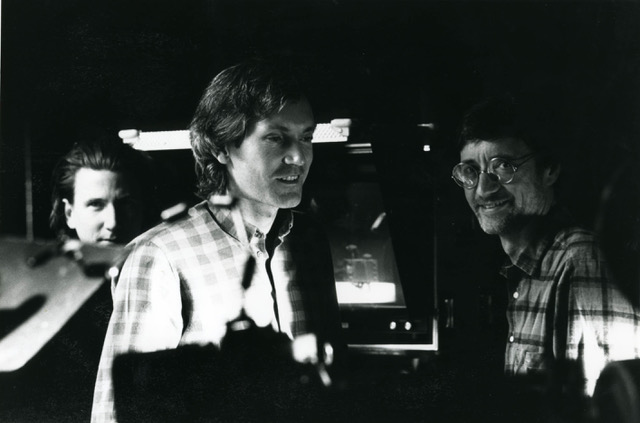

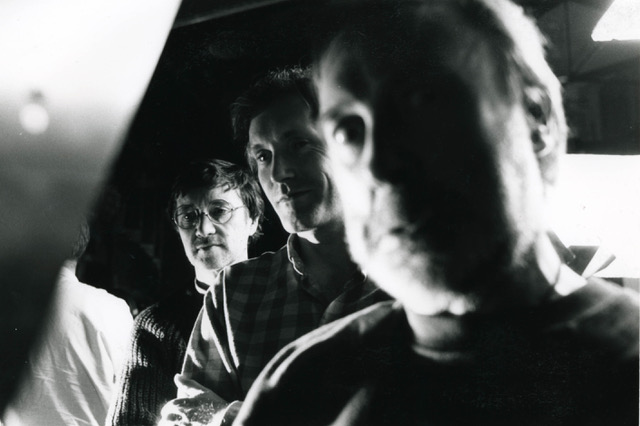

If you want to see the work we discussed, most of it can be found on the Gorgeous site, where Frank still has an archive. Meanwhile, here are a few pictures from his own personal collection (including Frank Budgen’s storyboard for Playstation Mountain):

and then cloaked this with 150 stunt men to get the final tip of the Mountain shots, filmed from a crane on the roof and a helicopter. I was

happy when we got the whole unit safely to the ground that evening.

We had over 700 stunt man days on that job, and 1400 extras.”

He’s a lovely bloke. We had a lovely chat. Enjoy…

iTunes link, Soundcloud link, and button you can press right here (Because of the fun weirdness of WordPress, if you like the direct play button, there will be a separate post just above this one with the second part of our chat. iTunes and Soundcloud will have both parts):

A lonely mother gazing out of the window, staring at a son that she just can’t touch. If at any time he’s in a jam, she’ll be by the weekend.

Remember I’m the same one that they used to laugh at. Now they pay me for a feature just to school em like a teacher. Had a dream like Martin Luther having flashbacks. Now it’s translated here to the weekend.

Picking 24 billion cherries in eight weeks.

A handy IMDB rating breakdown for all episodes of a series.

The Hendrix of the ukelele:

How Tarantino keeps you hooked:

Oh, the lack of humanity.

Two joys have recently entered my life.

The first is a subscription to The Criterion Channel: $99 a year for unlimited access to many of the greatest films of all time. Not so much the western ‘classics’, such as Casablanca or Citizen Kane (although some of those are included); more the global greats from Fellini, Godard, Sembene, Ozu etc.

I grew up with a movie-fanatic brother, so I saw a lot of those films when I was a teenager, but I hadn’t seen as many in recent years. It’s been easier to experience whatever America’s studios have to offer, especially when taking the kids, but newly housebound, I decided to check out this alternative source of cinematic brilliance, and it’s been a delight.

These films were generally made by artists whose intention was to connect humanity to itself. Super-powered Avengers have been swapped for terminally ill Japanese bureaucrats and I can’t tell you how good that feels.

Beyond the plots, these works of art were all shot on film, usually without special effects, in some form of reality, with actors conveying relatable emotions. And that’s left me feeling connected to the humanity of it all, to the shared experience of being alive with the rest of you.

The second joy is radiooooo.com (article about why it is amazing here), a website that allows you to select any decade and country to hear the music that, for example, was popular in 1965 Mozambique or 1948 Colombia.

It’s been equally fulfilling, as I’m now discovering an unexpected love of Nigerian cha-cha and the prog rock of 1970s Iran.

Perhaps it’s the confirmation that I’m in some way connected to people who lived thousands of miles away from me before I was even born. Perhaps it’s the idiosyncrasies of music played by real people on real instruments, not autotuned and compressed to sound like last week’s chart success. Whatever it is, it feels closer to something essential about being human.

These two portals entered my life around the same time that I read an article by Paul Burke on the benefits of the account management department. I commented:

Excellent, as usual. In addition, this is now heading towards the inevitable use of AI and algorithms to do the ‘Project Management’ job. You can see the spreadsheet you’ll fill in at each stage of the creative process, until all the work is ready to be sent to the client’s dedicated ShareTransferBox, where they deliver their annotated feedback based on another algorithmically-designed set of agreed-upon criteria. (None of that is an exaggeration or joke, by the way. It’s really coming to an ad agency near you.) Suicide emoji goes here.

Shit! My wife just showed me Jira, which is exactly that.

To which Paul replied:

Account handlers brought creative and strategic empathy to a “drop in” whereas project managers don’t. Unless you bring humanity, you will get automated.

It felt like an interesting coincidence.

I don’t know how lockdown has been for you, but I think for many of us it has meant a literal distancing from other people. Lots of us have therefore been reminded of how fundamentally we need contact with the other members of our species; a dose of humanity. Sure, there’s the obvious way of making that happen – a drink or a walk with a friend – but art exists because it can connect us to millions of people at the same time. That’s why it means so much to us.

But the last 10-15 years have left us sinking further and further into a kind of android existence, where we’ve become part computer to experience a regular life (the ubiquity of mobile phones, social media, Zoom, Kindle, Spotify, Airpods etc.). Each one of these alone isn’t necessarily problematic, but they have all encouraged us to trade connection for convenience, and when you put them all together, that trade takes a lot out of us.

Yes, albums, letters, landline phone calls, books etc. are more inconvenient to use or produce, but that’s what makes them great. The corollary of ‘easy come, easy go’ is ‘difficult come, difficult go’, where you treasure things that are earned, or hard-won. Of course, having every song ever made in a little box in your pocket is much ‘better’ than having to spend £12 on a CD, hoping that the other nine tracks are going to be worth the expense. But it’s also worse, because you don’t give the whole album enough of a chance for the songs to grow on you. Pressing a button is easier than going over to a shelf, finding an album, removing it from its sleeve, placing it on a record player, dropping the needle and having to get up and flip it over after every five songs. So why do I prefer playing records?

If you read a book on Kindle you can carry 500 hardbacks in your handbag, but… no one knows what you’re reading, so you no longer have that moment of connection on the bus or by a hotel swimming pool, where you can go up to someone who’s reading the same book you just finished and have a chat about it. You have became more remote from all those people. You experienced less humanity.

So now we also have remote connections at work, where we use algorithms designed by someone in Silicon Valley to decide how we should relate other people, a skill many of us had mastered over years of trial and error: no more than 20 words on a social post image, no more than six seconds of content lest people get bored, the message must appear in the first three seconds because that’s when uninterested people switch off… Never mind that billions of people have enjoyed more than 20 words, sixty seconds of content and messages that come as a punchline/surprise at the end. The algorithm has spoken, and we are now just blobs of organic matter whose job is to obey the computer-ordained diktats of consumption.

And the point Paul was making, that more ostensibly ‘efficient’ systems will drain the creative process of humanity, is the final part of the circle. Use Jira and fill in boxes one (three second intro) through seventeen (algorithmically-approved endline of no more than seven syllables). Then wait for for client feedback on Slack, or the junior strategist’s notes on the Google Doc, and act upon them before the prescribed three-hour deadline or your surgically-implanted microchip will deliver a ReminderShok® at five minute intervals until the AI ProjectBot® deems your response sufficiently optimised within agreed-upon guidelines.

Will such distance from humanity improve anyone’s ability to connect to other humans, the better to enroll them in liking a product or service?

No. That’s it. No. Nope. No way. Uh-uh. Not a chance. No hope and Bob Hope, and Bob Hope Just left town. Norfolk and Chance.

So here we are, deep inside the removal of humanity from all areas of life. If you’re wondering why it’s been happening, it’s simple: people (particularly creative people) are messy, unpredictable, uncontrollable, difficult, inconvenient and sometimes lazy. So if you’re a company who wants to maximise profits, you’ll want to minimise tedious, expensive, annoying idiosyncrasies and turn your staff into compliant robots, churning out exactly what Big Brother requires, exactly when he requires it.

But…

We’re also imaginative, inventive, brilliant, charming, funny, smart, unpredictable, warm, humane, happy, sad, boring, exciting and everything else that makes us want to spend time with each other.

We are life, and that means taking the difficult with the easy and the rough with the smooth, for you don’t get the highs without the lows, and those ups and downs are always better than the straight line of nothingness that android life provides.

So what can you do? Well, there are myriad ways of sneaking the analogue world into the digital universe. My favourite is refusing to work on Slack because it’s distracting (it is! How does anyone get any work done with the constant bings? What’s wrong with email?). Same with Google Docs. Make a pdf and have a separate communication with your CD, or go and find him or her and have a chat IRL (as the kids say). Lean towards albums. Go and see a real old movie at the NFT (or local/lockdown equivalent). Enjoy a real live gig (or lockdown equivalent). Buy a Super 8 camera or an old SLR and explore light, depth and human expression.

Then go and hug someone. Or kiss someone. Or have some good old fashioned sex (or some new-fangled sex).

The more humanity you experience, the better you’ll feel.

It’s official: ads are worse than they used to be, and if we don’t address that we’re all screwed.

There’s a crisis in advertising creativity.

I know what you’re thinking: “Yes, Ben. I’ve been reading your blog for a while. That’s all you ever bang on about. Give it a rest.”

But this is different. It’s ‘official’ because it’s confirmed by a report from the IPA. (The report is actually a year old, but nothing has improved.)

Tempted as I am to simply cut and paste the whole thing here, I’ll leave you to click on the above link. But for the time-poor among you, here are some highlights:

The report The Crisis in Creative Effectiveness covers almost 600 case studies from 1996 to 2018 and is a follow-up to the IPA’s 2016 publication Selling Creativity Short that warned of the dangers to creative effectiveness posed by short-termism in marketing and highlighted a misunderstanding of how brands grow.

According to revered effectiveness expert and report author Peter Field*, creatively awarded campaigns are now less effective than they have been in 24 years of data analysis and are now no more effective than non-awarded campaigns.

The Report also reveals the continuing decline in the efficiency** of creatively awarded campaigns. Over the pre-crisis period 1996-2008 creatively awarded campaigns were around 12 times as efficient as non-awarded ones, but over the period from 2006-2018, as the crisis developed, this fell to below four times as efficient. It continues to fall and creativity is almost certainly delivering no overall efficiency advantage today.

You might recall how I have often posited that great advertising generally slowed to a trickle around 2008 and (Cadbury’s Gorilla). Yes, of course there have been great ads since then (I’m looking at you, Old Spice, Dumb Ways To Die and You Can’t Beat A Londoner), but the rate has slowed considerably. I blamed that on the rise of digital/social/search, but there was also a monumental economic crash at the end of that year, so it may have been a perfect storm of newly-prioritised short-termism, coupled with the means to address it in the least creative ways possible.

This report suggests that short-termism in advertising and, crucially, the awarding of short-term ads is an ouroboros that means we’re stuck in a short-term mindset that will eventually consume itself, leaving behind nothing of value.

As the report states:

“…left unchecked, the catastrophic decline in creative effectiveness will ultimately weaken support for creativity amongst general management. Money spent on creativity will become ‘non-working’ budget and will be cut.”

So if creative ads don’t actually work any better than non-creative ads (eg: the stuff you find on Facebook, and Google’s SEO fun), no one is going to take the time, effort or money to support them.

And that’s bad, isn’t it? Do you want to live in that world? More to the point, do you want to work in the advertising industry in that world? Of course you don’t. But if you’re not sticking up your hand and objecting to that world, either as a creative, CD or member of a jury you are making that world happen.

To be clear, I’m not blaming you. I’m certain I’ve done this myself (although I have also railed against it). But here’s where the rubber hits the road. If you can’t do something about this directly, show this report to someone who can. Enroll a client in the benefits of longer-term thinking. Petition D&AD to split awards into those for short-term ads (prize: some used loo roll), and those for long-term ads (prize: a bright shiny trophy). Question the legitimacy of a brief that has an ephemeral, ineffective short-term gain as its goal…

Otherwise, we’re going to be in more trouble than we are right now, and right now we’re in a lot of trouble.

Somebody once told me the world is gonna roll me. I ain’t the sharpest tool in the shed. She was looking kinda dumb with her finger and her thumb in the shape of the weekend.

Archives