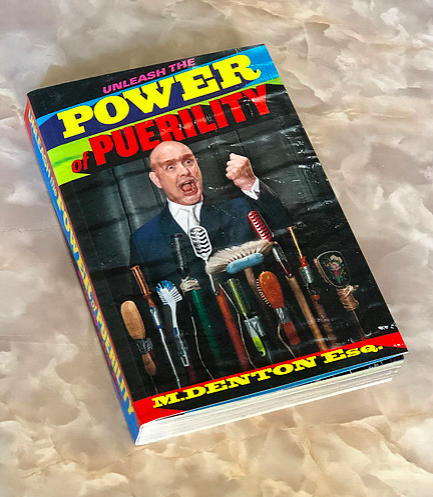

ITIAPTWC Episode 58 – Mark Denton would like you to buy his book.

Mark Denton has been many things: art director, creative director, director, founder, graphic designer… But he’s now an author.

I know he’s done other interviews (and this one) for Unleash The Power Of Puerility, but there were still a few things I wanted to know.

The main one was: how do you make a book? I mean, if you have an idea of a book you’d like to put together, where do you start? Well, allow Mark to explain.

In usual MD style, we also discuss other things, such as the time he had to go to New York to think of an idea for an ad, then came back without one (until he jumped in the cab back from Victoria). And why he chose ‘Can I Kick It‘ for that Nike ad (spoiler alert: they’re both based around kicking things).

Anyway, he’s as entertaining as usual.

But don’t forget to buy his book.

Here’s the link to iTunes, the Soundcloud link, and the direct thing where you can just press play: