This ad is great. Here’s why:

Given that my most recent Creative Review column suggests that there is no objective way of measuring advertising quality, I thought I might take this opportunity to ironically explain why one particular ad is unarguably, totally and utterly ’great’.

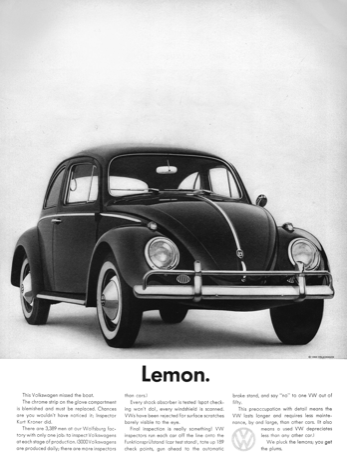

The ad in question is this one for Communion from Uncommon:

So why is it good?

- It stands out. As old Mr. Bernbach used to say, if nobody notices your advertising, everything else is immaterial. I’ll just repeat that: if nobody notices your advertising, everything else is immaterial. I mean, sure, that’s obvious, but you wouldn’t think so from watching most of the ads that slide past your consciousness as if they never happened. This stands out and it does it in two ways: it’s different to the other ads in the break (or LinkedIn/Twitter/Facebook feed), and it’s different to other financial services advertising. And with that grinding rock guitar and grimy black-and-white aesthetic, it’s literally made to be noticed. Big tick.

- It’s constantly engaging. There’s a V-sign, which is intriguing, but there’s also a list of things to which you might like to apply that gesture. What’s this all about? What’s next? Whose fingers are they? Do I agree? Who is running this ad? Is it an ad? Why is it black-and-white? So many unanswered questions to keep you interested. And those unanswered questions will provide the depth that will make people pay attention to it again the next time it appears.

- It has a satisfying conclusion, by which I mean you don’t feel the preceding 50 seconds were gratuitous. The answer is a good one, and it makes sense. You can’t really disagree because you think about this kind of thing all the time: ‘If only I had X amount of money, I could living in a better place, and I wouldn’t have to listen to that arsehole, or get up at that time of the morning etc.’. This is ‘If only I could win the lottery’ but in a way that is attainable. Money IS freedom, and this is what that freedom will get you. You don’t open a savings account; you open the chance to move out of your parents’ house.

- It has a great strategy. Financial services strategies are usually along the lines of ‘save for a rainy day’ or ‘feel secure with a blah blah pension’. Both of those are negative and dull. This is positive and inspiring. And great strategies are rare these days. They usually say things like ‘Live your best life with X’ or ‘Unleash your potential with Y’. Generic, forgettable, easy to ignore. Not like this, which is the opposite of those three things.

- The branding is excellent. It’s all irreverent attitude and block capital letters. You are not going to confuse it with Prudential or Aviva. And if you’re young, and not even thinking of this category, this will be the financial services company for you. Sure, it will put some people off, but this isn’t for them, and that stance will get them bigger, more devoted fans. They’re not growing the category; they’re growing themselves, and as a challenger brand, that is an essential distinction.

- It’s topical. People are brassic. The mismanagement of Britain’s finances by the current government has left millions tightening their belts. Fuel prices, inflation, mortgage rates… fuck all that. But what’s the solution? Communion. ‘Save Enough To Save Yourself’? Damn right.

And that’s why this ad is great.