Should I call this post ‘double dave’ and enjoy the alliteration, or ‘double trott’ and enjoy the ‘double top’ pun? (enjoyment levels quite low on both.)

For those of you who need a primer in the basics of advertising, Dave Trott has kindly offered everything you need to know in one simple TED talk:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S0gZfhkoi1E

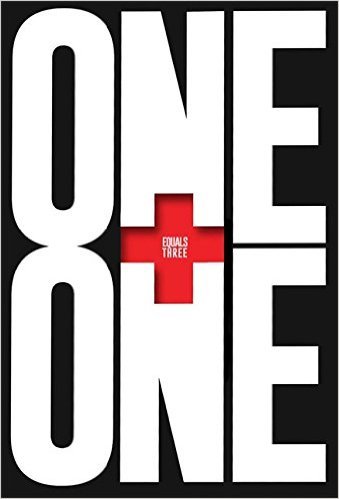

And when you’ve finished that you can read his new book, 1+1=3:

It’s entertaining, thought-provoking and comes in lovely little bite-sized chunks (I’m sure it’s just a coincidence, but those chunks seem to last about as long as a poo).

Buy it here and have a slightly better life.