Where is planning heading?

One of the great things about subscribing to Creative Review is the access it gives you to the mind of Paul Belford.

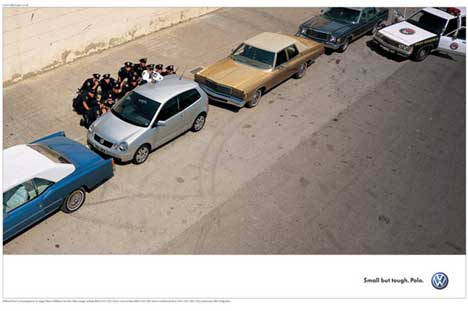

I recently read back through all his columns and discovered a very interesting point that bears repeating: some of the greatest advertising of all time was created without the benefit of planners. He was referring specifically to the early VW ads such as Lemon and Snowplough, but he could have included anything brilliant created before 1965-8, when the discipline was formally invented in London by Stanley Pollit (the ‘P’ of BMP). Surprisingly, planners didn’t really reach America until the early 1980s, so any great US ads created before then came to life without the help of that department.

(Then again, there were also plenty of crappy ads created in that time. Was that down to poor strategic input? Possibly…)

The need to consider who might like to consume the thing you want to sell, how best to address them and the ways in which your competitors present themselves are basic elements that didn’t magically materialise in the late 1960s. But at that point a degree of formality was deemed necessary, so the industry decided to make planning a specialism, and handed responsibility for it to a separate collection of people in a new department.

The reason I bring this up now is that we appear to have come to an unexpected schism: the idea of doing away with planning its current form has been mooted by no less an industry figure than Mark Pritchard, Chief Brand Officer at P&G. He has advocated for the discipline to be handled in-house, with its resources instead allocated to the creative department.

Further commentary has come from Andy Nairn, founding partner (on the planning side) of Lucky Generals. Understandably he has defended the his turf, asserting that planning strengthens the voice of the consumer, one that often gets drowned out by the agency perspective. That makes sense, but he also acknowledges that some planners can be ‘speed bumps’ and ‘resistors of change’ (to be fair, those two categories also exist in creative and account management).

It’s also worth mentioning this crisis of confidence is happening a mere decade after planners were insisting they be granted admittance to the edit suite. Apparently this would allow them to give their valuable input to parts of the creative process from which they had been hitherto forbidden.

So where is this all heading? A reduction in the number of planners? A redistribution of planners’ wages throughout the creative department (winky emoji)? A redistribution of planners’ responsibility amongst Comms Planners, Media Planners and Client Brand Guardians? A redistribution of the three months it takes planners to write a brief back into the creative process? A new way for strategic knowledge to permeate through creativity?

Who knows? I still think there’s great value to be gained from strategists who can analyse the heck out of a business and/or category, offering insight and rigour that uncovers hidden gold. But that only seems to be a small part of the current job, which might explain why the discipline in its current form is going through something of an identity crisis. In addition, the creative department, and advertising in general, have been going through their own ten-year malaise, so planning difficulties might be just one symptom of a more widespread disease.

The offerings of Facebook and Google circumvent every part of the industry, leaving us all fighting for our positions, possibly at the expense of each other’s.

A wise man once said that a creative who works without planning is like someone trying to reach a destination without the aid of a map. Good point, but it feels like the transition from Ordnance Survey to Sat Nav has not been without its hiccups.